27. Trauma Informed and Trauma Responsive Care

Written by Anna Cheetham and Katie Mottram.

Greek (τραῦμα) ‘wound’

“Trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically or emotionally harmful or threatening and has long lasting effects on the individual’s functioning and physical, social or spiritual wellbeing.”

- SAMHSA, 2014

“Trauma refers to the way that some distressing events are so extreme or intense that they overwhelm a person’s ability to cope, resulting in a lasting negative impact.”

- UK Trauma Council

Introduction and overview

This paper offers an introduction to trauma informed practice with a gentle approach, recognising that we are all starting from different places in our work and personal journeys, and we all have much to learn. The paper is intended as a springboard to carry into your areas of influence to initiate conversations, create new ideas and to stimulate further dialogue. We provide an introduction to the principles of trauma informed practice, rooting it within the history and current practice in mental healthcare. Following this, we explore historical concepts of trauma, then move to a transdiagnostic framework to support trauma informed practice.

This framework communicates the importance of recognising the reach of trauma within human experience, understanding how it can manifest, and the ways of relating that are required in trauma informed, or better still, trauma-responsive, care. We emphasise what needs to be considered in order to resist re-traumatising those coming into contact with services. We also consider how trauma is rooted in wider systems and differs through cultures. We suggest practical guidance for teams, organisations and systems who wish to develop more trauma informed and trauma-responsive ways of working, and ultimately, environments that have the potential to heal.

We accept that the word trauma has medical connotations for many, which may be problematic in terms of the approach we describe. Trauma can be taken to refer to specific events which have consensually been agreed to be traumatic. However, in this briefing paper we maintain an open and exploratory approach to considering the diverse impacts of the variety of threats to psychological and physical safety which cause trauma, as well as the contexts and interventions that can offer protection from adversity.

“‘When a flower doesn’t bloom, you fix the environment in which it grows; not the flower’. ”

Historical concepts and understandings of trauma within the Western Mental Health field

Given its constant presence in the narratives of human history, it might come as a surprise that the word ‘trauma’ did not enter into the language of mainstream mental health and psychiatry until relatively recently. The diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) was not incorporated into the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) until the 1980’s and made its first appearance into the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM), the US equivalent, in the 1990s. This is relevant as these are the dominant publications that aim to define experiences that get called ‘mental illness’, drive discourse, research, and influence our thinking and language around mental health.

Prior to this, manifestations of trauma have had varied descriptions such as ‘shell shock’, ‘combat fatigue’, and ‘hysteria’, which became subsumed by a wide variety of diagnostic categories. Within trauma definitions, the recognition of what might constitute trauma was narrowly defined, often relating to single events of a catastrophic, life-threatening nature such as combat trauma, natural disasters, road traffic accidents and severe assaults including threat to life. Core symptoms included re-living, avoidance, autonomic nervous system arousal and hypervigilance.

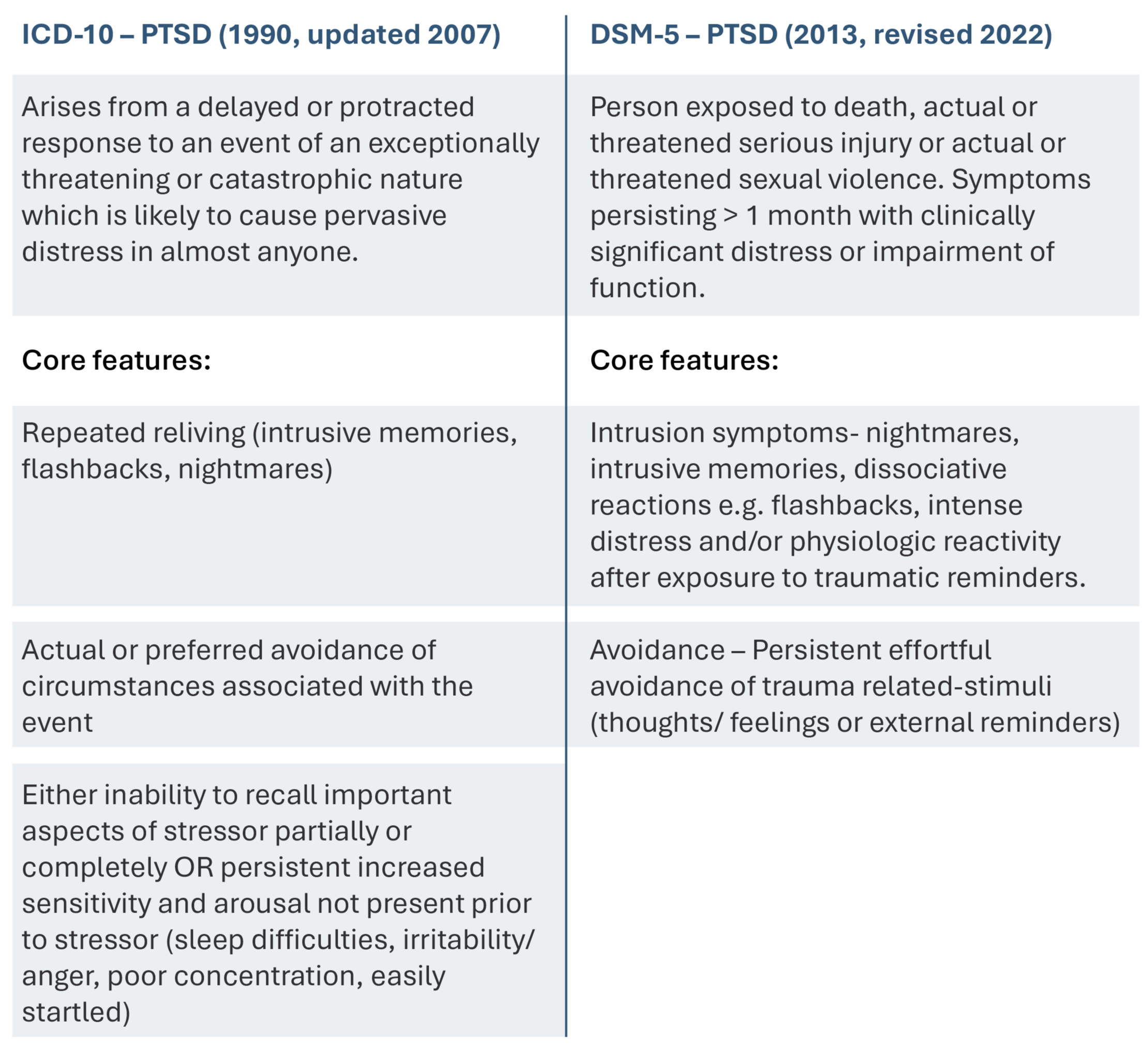

PTSD Diagnostic Criteria: Side-by-Side Comparison

Below are the official criteria for diagnosing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) according to two leading manuals used by clinicians worldwide. These boxes show content from the ICD-10 and DSM-5.

Box 1: PTSD Diagnostic Criteria: Side-by-Side Comparison

These, for many, fail to capture a similar constellation of ‘symptoms’ and difficulties, that are not born out of a single catastrophic or life-threatening event, but adverse experiences or repeated events that undermined, threatened, disempowered or disconnected individuals from a sense of belonging and safety. The work of critics of these narrow concepts, who recognised wider impacts of developmental and sexual trauma, such as Judith Herman (1992) eventually led to the contributors creating an additional category in the ICD 11; Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (cPTSD).

In 2022, the World Health Organisation included Complex PTSD (cPTSD) in the ICD-11 to describe the effects of repeated or long-lasting trauma.

ICD 11 (2022) cPTSD

Exposure to an extremely threatening or horrific event or series of events with significant impairment in functioning > few weeks.

The criteria are shown below

Core symptoms of PTSD in addition to the following:

Problems in affect regulation (irritability/anger/ feeling numb)

Diminished self belief (worthlessness, shame, guilt, feelings of failure relating to event)

Difficulties sustaining relationships and feeling close to others

The DSM-5 did not follow suit in creating this additional diagnostic category, however, it changed considerably from previous editions with the relocation of PTSD from the anxiety disorders category to a new diagnostic category ‘Trauma and Stress-related Disorders’ and the elimination of the requirement for trauma to involve ‘actual or threatened death, serious injury or sexual trauma’.

Whilst diagnosis can play a role in understanding and developing evidence-based treatments, a comprehensive understanding of the impact of trauma in all its forms, and what is required to heal, must extend beyond diagnostic categorisation.

The recognition within the ICD and DSM of the role of trauma does not in itself inform trauma informed approaches. In fact, for some, positioning trauma responses as ‘disorders’ is at odds with the values of a trauma informed approach, which invites us to understand ‘symptoms’ as attempts to cope. Moving away from diagnostic or deficit based approaches and toward more trauma informed ones requires careful and sustained work at both individual and system levels. In the following sections, we outline a trauma informed approach including the values that underpin it and practical ways to adopt it in practice. We have used the 4 R’s (SAMHSA, 2014) to structure these sections as they provide a helpful transdiagnostic framework to guide us through the stages of trauma informed care.

The pillars of trauma informed care ‘The 4 R’s’

Figure 1: Adapted from SAMHSA’s Guidance for a trauma-informed approach (2014)

Realise

Realise the complex and widespread impact and prevalence of trauma. What causes traumatic stress for one person may not for another, dependent on context and individual factors.

Recognise

Recognise the signs of trauma. Be curious about the wide-ranging manifestations of trauma and adversity with responses that encompass psychological, emotional, relational, behavioural and cognitive domains.

Respond

Respond with trauma sensitive principles of safety, trustworthiness and transparency, collaboration and connection, empowerment, voice, choice, and cultural sensitivity. Responding with compassion and curiosity without judgement.

Resist Re-traumatisation

Know how policies and practices can affect the wellbeing of staff and people who use services by unintentionally resonating with past traumatic experiences, exacerbating and adding to trauma. It is important to create psychologically informed environments (PIEs) and relationships that support wellbeing and avoid re-traumatisation for everyone involved.

Realising

Trauma and Trauma informed Care

The language of trauma informed care has become part of the fabric of mental health in recent years. In fact, trauma informed care has extended its relevance beyond mental health settings to wider public services, including general healthcare, education, social care, emergency services, prison services, homelessness and beyond, to encapsulate its relevance to all humans at all stages of life. Indeed learning, adaptation, and growth as a response to adversity can be considered a constant in the natural world, and from this we can reflect upon the opportunities that come from adaptation and post-traumatic growth.

Trauma can impact anyone, from any background, and can affect individuals, families, groups and communities, especially where they don’t have adequate understanding, support or resources to cope. Gabor Maté, a Canadian Physician and thought leader with extensive expertise in childhood development and trauma, describes the ‘wound’ as not what happens to you, but ‘what happens inside of you as a result of what happens to you’ (Maté & Maté, 2022). In contrast to the early definitions of trauma in the ICD and DSM, he emphasises that developmental trauma (which occurs in childhood) is relational; that wounding comes from a rupture, or a lack of security within primary attachments that prevent a sense of safety from developing - safety being a basic requirement for survival.

Many adverse events that may be traumatic are relational and societal at their root, and involve a threat to physical and/or psychological safety, identity and connection: the belonging that is required for human survival. Understanding trauma requires the recognition that it is not the events themselves, but the individual’s unique experience of them and how this is responded to by others, that creates the context that shapes the psychological and physiological impact of the event(s).

A trauma informed approach transcends diagnostic pathways to encompass what is required to support humans who have experienced profound adversity, the nature of which may or may not be obvious to us as supporters. Trauma informed approaches invite us to consider the relational needs that individuals might have in order for them to recover and thrive beyond what has happened to them. The importance of how we ‘show up’ and relate, not just the interventions we offer, is central to this concept. Relational connection and attunement (Hübl, 2023) can act as a powerful, foundational ‘intervention’ in itself.

“Relationships are the agents of change, and the most powerful therapy is human love”

A trauma informed approach emphasises that humans are intrinsically resilient and have biologically inherited wisdom in how to survive. Those who have experienced and survived trauma may not always be aware of these inherent strengths, but they are undoubtedly present, as, like all living things, humans have an innate will to survive. Indeed, trauma responses are viewed by many in the field as helpful messengers, alerting a person to what has happened and the need for safety. This can also be considered in the context of learned wisdom in other cultures where what we might consider ‘symptoms’ hold different meanings and may not be pathologised, something that will be expanded on later in this paper.

Trauma exists on a spectrum. Not all events that have the potential to be traumatic lead to debilitating consequences. Some individuals may not be impacted by events that deeply impact others. This is dependent on multiple personal and external contextual and protective factors. Some may experience an event as traumatic but emerge with a deeper sense of purpose, improved relationships and a heightened appreciation of life (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). Others may be deeply wounded by less overtly severe events, such as constantly being criticised or feeling unseen, their emotions invalidated in childhood. This so-called ‘invisible trauma’ has been proven to also significantly impact the experiencer at a physiological level (Gamma et al., 2021). The physiological impact of trauma is also explored later.

The prevalence of trauma

In 2015, the World Mental Health Survey Consortium reviewed general population surveys in 24 countries with a combined sample of 68,894 adults. 70% of respondents reported a traumatic event, with 30.5% exposed to 4 or more (Benjet, Medina-Mora et al., 2016).

The original Center for Disease Control (CDC) Adverse Childhood Experience (ACEs) Study in the US found that out of 17,000 individuals, two thirds had at least one ACE, with over a quarter (26%) suffering physical abuse and a fifth experiencing some form of sexual abuse (Felitti et al., 1998). Surveys within English populations such as the Blackburn with Darwen study (Bellis et al., 2013) suggest around 1 in 10 have experienced four or more adverse childhood experiences, with nearly half of the population experiencing at least one.

1 in 5 adults experience domestic abuse during their lifetime, with 2.4 million adult victims - 1.7 million women and 699,000 men (ONS, 2021). A domestic abuse call is made to the police in the UK every 30 seconds - statistics from National Centre for Domestic Violence, Domestic Abuse Statistics UK (ONS 2021), (Violence against women & girls: Research Update (ONS, 2022), (Domestic Abuse Act, 2021: Home Office Policy Background). 53% of women who have identified mental health difficulties have experienced abuse (Scott & McManus, 2016).

The simultaneous experience of trauma and discrimination disproportionately affects minority groups, whether this is individualised (e.g. violence) or systemic (e.g. marginalisation or poverty). People from minority backgrounds based on characteristics such as race, immigration status, sexuality, gender identity, neurodiversity or economic disadvantage, are more likely to experience trauma. (Ford et al., 2015). The additional stress caused by marginalisation, discrimination, victimisation and lack of social support can interact with trauma to overwhelm a person’s capacity to cope. There are also increased rates of traumatic events and impacts within these groups. (Mongelli et al., 2019; Polanco-Roman et al., 2024; Cruz-Gonzalez et al., 2023).

The impact of the COVID pandemic worldwide is perhaps a trauma we can most universally relate to. This resulted in a 25% increase in the prevalence of reported depression and anxiety worldwide (WHO, 2022). There was also a profound impact on staff within the NHS of caring for and bearing witness to the impact for people using services and families over this period. Taking one NHS Trust as an example, 1137 staff accessed Humber and North Yorkshire Trust Staff-Wellbeing and Resilience hub over 1 year. Of these, 75.6% of nonclinical staff and 83.9 % clinical staff showed trauma-related symptoms (Professor Angela Kennedy National Trauma Informed Community Conference 2023. Original paper Elvin et al., 2023).

As might be expected given the impact of trauma on emotional health, the prevalence of adverse events and traumatic stress are increased in those accessing help from mental health services (Devi et al., 2019), with prevalence being particularly significant in inpatient populations. In one study, 97% of inpatients in a psychiatric hospital (n=139), had experienced at least one known trauma, and 69% had endured repeated trauma over a prolonged period (Floen & Elklit, 2007). ACEs have also been linked to an increased likelihood of experiencing anxiety and depression as an adult, with one study finding that young adults with higher numbers of ACEs were over seven times more likely to experience anxiety and depression than their peers (CDC, 2017).

The link between adverse childhood experiences and subsequent mental health challenges in adulthood is not a simple cause and effect relationship. Traumatic experiences can be mitigated by a person’s protective factors, including supportive relationships, acknowledgement of harm and opportunities to make sense of painful memories. Equally, individuals who cannot identify ACEs in their own childhoods may go on to experience significant mental distress as adults for a number of reasons which do not qualify as ACEs.

It is important to highlight that the number of people who have experienced trauma in childhood can often be underestimated because it is not routinely explored during the admission process or throughout treatment in mental health services, and there may be a lack of understanding about what constitutes trauma. A further study showed 82% of psychiatric inpatients disclosed traumatic experiences when asked, compared to only 8% volunteering this information without being asked (Read & Fraser,1998). On average it takes between 17.2 and 21.4 yrs before victims disclose childhood sexual abuse (Steine et al., 2016; Easton, 2013).

If we take the above information into account, it is clear to see that trauma is more prevalent amongst the general population than socially ingrained stereotypes about people with mental health problems suggest. Given the high prevalence of adverse events that can be associated with trauma responses, it is vital that trauma responsive systems embrace the concept of universal precaution, acting from the assumption that everyone we interact with may have experienced trauma. This heralds the need for a paradigm shift away from a focus on asking “what is wrong with you?” to adopting a curiosity and sensitivity to “what has happened to you?”, and the impact that trauma might have had, and may still be having now.

Recognising

The Impact of Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

The groundbreaking CDC- Kaiser Permanente Adverse Childhood Experience (ACEs) Study (Felitti et al., 1998) identified that ACEs increase the risk of a person developing a wide range of physical and emotional health difficulties due to the ongoing impact of trauma over the life course (figure 2). ACEs can be associated with addiction and poor social functioning (Ashton et al., 2016) and are strongly associated with increased risk for experiences described as psychosis in population studies (Varese et al., 2012). In Felitti’s study those with 6 or more adverse childhood experiences were found to have up to 20 years reduced life expectancy.

The discovery of the significant relationship between childhood trauma and physical and mental health outcomes has been repeated in numerous subsequent studies e.g. (Bellis et al., 2014; Hughes et al., 2017). It is recognised, however, that individuals can have buffering factors that protect from trauma, and these are often interpersonal and relational. Research suggests that compassion for oneself and from others through connectedness and empathy plays a key role in modulating risk for adverse health outcomes in the context of trauma (Cristea et al., 2014; Wesarg-Menzel et al., 2024, Brinckman et al., 2024).

Figure 2: ACEs Pyramid adapted by CDC (Public Domain). Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons: ACEs Pyramid.

Adverse Childhood Experiences can include:

Emotional abuse

Physical abuse

Sexual abuse

Emotional neglect

Physical neglect

Witnessing domestic violence

Household substance misuse

Household mental health issues

Parental separation or divorce

Incarcerated household member

Bullying

Witnessing violence outside the home

Witnessing sibling abuse

Experiencing discrimination

Being homeless

Natural disasters

War

Above is a list of some experiences that are recognised to be Adverse Childhood Experiences within studies on this topic.

Recognising how trauma impacts the mind and body: Understanding the neurobiology of Trauma

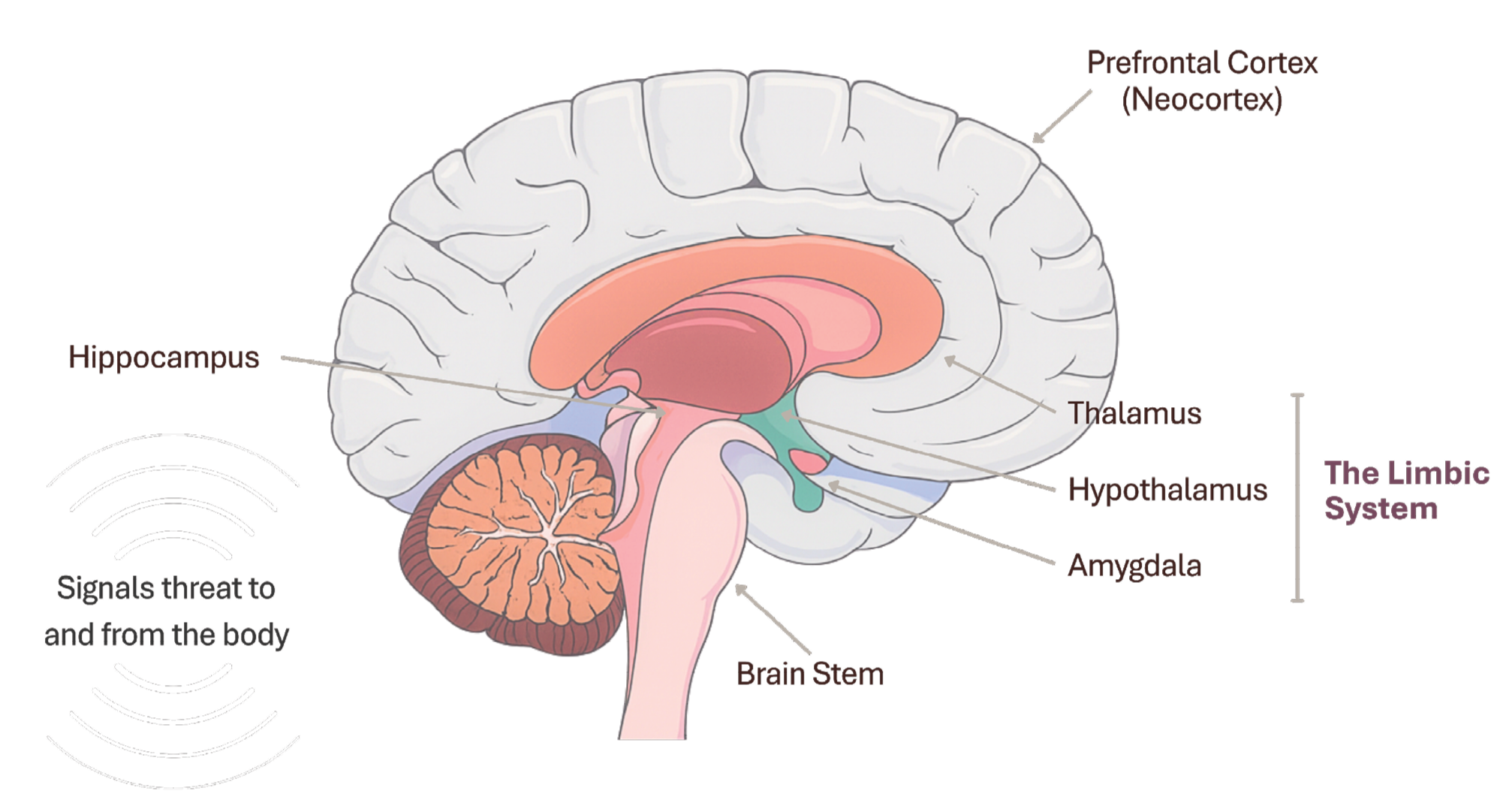

Figure 3: an illustration of the different parts of the brain

Our neurobiology adapts as a result of being in an unsafe or neglected environment, with our more primitive unconscious ‘survival brain’ dominating in these situations. Trauma impacts the brain by activating the ‘fight/ flight/freeze’ responses, primarily through the more primitive back brain and limbic system, the amygdala acting as the brain’s threat detection system, a smoke alarm of sorts. This part of the brain is designed to ensure survival through unconscious reactions.

Trauma makes the brain hypersensitised and instinctively vigilant to predicting threat although unsophisticated in assessment of actual threat vs safety. When the body or senses experience something that resonates with past adverse experiences or predicted patterns of risk the amygdala triggers the release of stress hormones such as cortisol. This rapid emotional response occurs before the rational, thinking, problem solving prefrontal cortex is able to process events or consider the consequences of responses. Indeed, when in this threat/ survival response the ‘thinking’ frontal lobe is offline creating a degree of cognitive impairment and disconnect.

This is relevant to how we approach people who feel threatened or are dysregulated in fight/ flight freeze. Negotiating, giving instructions or trying to problem solve may not be an effective approach. Intervention to create psychological and physical safety, connection, co-regulation and holding space to support and enable nervous system regulation first can facilitate more meaningful and helpful interaction by bringing the frontal thinking brain back on-line.

The body holds trauma as somatic memory (Porges, 2011), expressed through bodily reactions to perceived threat, which may be engrained over time where there is persistent or repeated threat, initiating long-term conditioned responses.

As part of the fight/flight threat response heart rate increases, breathing quickens, muscles tense, there is increased alertness and energy. If prolonged however this can be associated with fatigue, digestive problems, insomnia, memory issues etc.

The Vagus Nerve, plays a key role in trauma responses as well as the ‘rest and digest’ responses to conserve energy when feeling safe. Vagus, meaning ‘wander’ in Latin, is the longest and most complex cranial nerve extending from the brainstem and ‘wandering’ down the body connecting the brain to the throat, the heart, the lungs and abdominal organs. It is a two-way communication composed of approximately 80% of nerve fibres dedicated to communicating sensory information from the body’s organs, to the brain, alerting it to changes in the body. Around 20% of fibres send motor commands from the brain to the organs. The body and brain are therefore both key players in the experience of trauma.

The body can also communicate stress in additional ways. There is evidence suggesting the gut microbiome may contribute to traumatic stress responses influencing inflammation and neurotransmitter signalling (Ke et al., 2023).

Trauma and its accompanying sensory overload can impact individuals on many levels. People may struggle to recognise or regulate emotions, be reactive, experience dissociation (disconnect the thinking mind from bodily responses), and cognitive function may be impaired as the survival brain kicks in. These natural responses may inhibit attachment, impair the ability to empathise or mentalise and create instability within relationships with oneself and others, and can also lead to misinterpretation of neutral cues e.g. experiencing facial expressions as hostile (Catalan et al., 2020).

With improved awareness and connection to the body, perceiving these responses as bringing meaning and viewing them as helpful messengers informing us about what makes us feel unsafe, we can support a deeper understanding. Learning how to support regulation in the body can therefore also offer a path to recovery and speaks to the importance of co-regulation and attunement with those offering care. These concepts will be explored later.

Trauma in our early relationships

Within the womb, the first experiences a child has are influenced by the experience of connection to the mother. A developing baby is shaped by the maternal environment, where the foetus can respond to maternal stress and placental transmission of circulating hormones such as cortisol levels. Studies have demonstrated an association between neuroendocrine alterations (alterations in the cells that make and release hormones) in mothers who have experienced persistent abuse in their own childhood with the potential to impact the environment in which baby develops (De Bellis & Zisk, 2014).

There are also epigenetic influences within this intimate connection. Epigenetics describes how our interaction with our environment and social experiences can cause changes that influence gene activity, creating variations and diversity in gene expression without altering the DNA sequence, effectively switching genes on or off. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the effect of traumatic stress can be transmitted to subsequent generations, even when these generations are not directly exposed to the original traumatic event (Franklin et al., 2010).

The brain is particularly sensitive to environment during prenatal and early years. The brain’s ability to change in response to experience is called ‘neuroplasticity’. In the first years of life the brain develops at a rapid rate, creating billions of synapses. Life experiences determine which synapses are strengthened, and this increased neurogenesis and neuroplasticity is key to a child’s ability to learn and adapt to their environment.

Studies of the offspring of the September 11th World Trade Centre attacks, Holocaust survivors and those displaced in World War II, show intergenerational effects from both maternal trauma in pregnancy and preconception that predisposed offspring to altered neurobiology and stress responses (Wittekind et al., 2010; Yehuda et al., 2005, 2008, 2016).

Research suggests that from birth, the importance of connection, being responded to, and the co-regulation of nervous systems, helps to shape our neurobiology, our sense of self and our sense of the world. We have evolved beyond social connection and belonging being attained from strength and safety in numbers (Dunbar, 1998). Before regulation is developed, an infant’s nervous system is co-regulated by connection and attunement to the caregiver. The child learns through this repeated act how to self-regulate, to gain a sense of self in relation to another and a safe foundation to develop from. If, however, a child grows up in an unsafe environment or where these needs cannot be met, the child will adapt to try and achieve safety and gain connection. Trauma can therefore also come from neglect, disempowerment, disconnection, and lack of validation of identity or emotional responses. It is not only what has happened but also what has not happened to allow a sense of safety to develop.

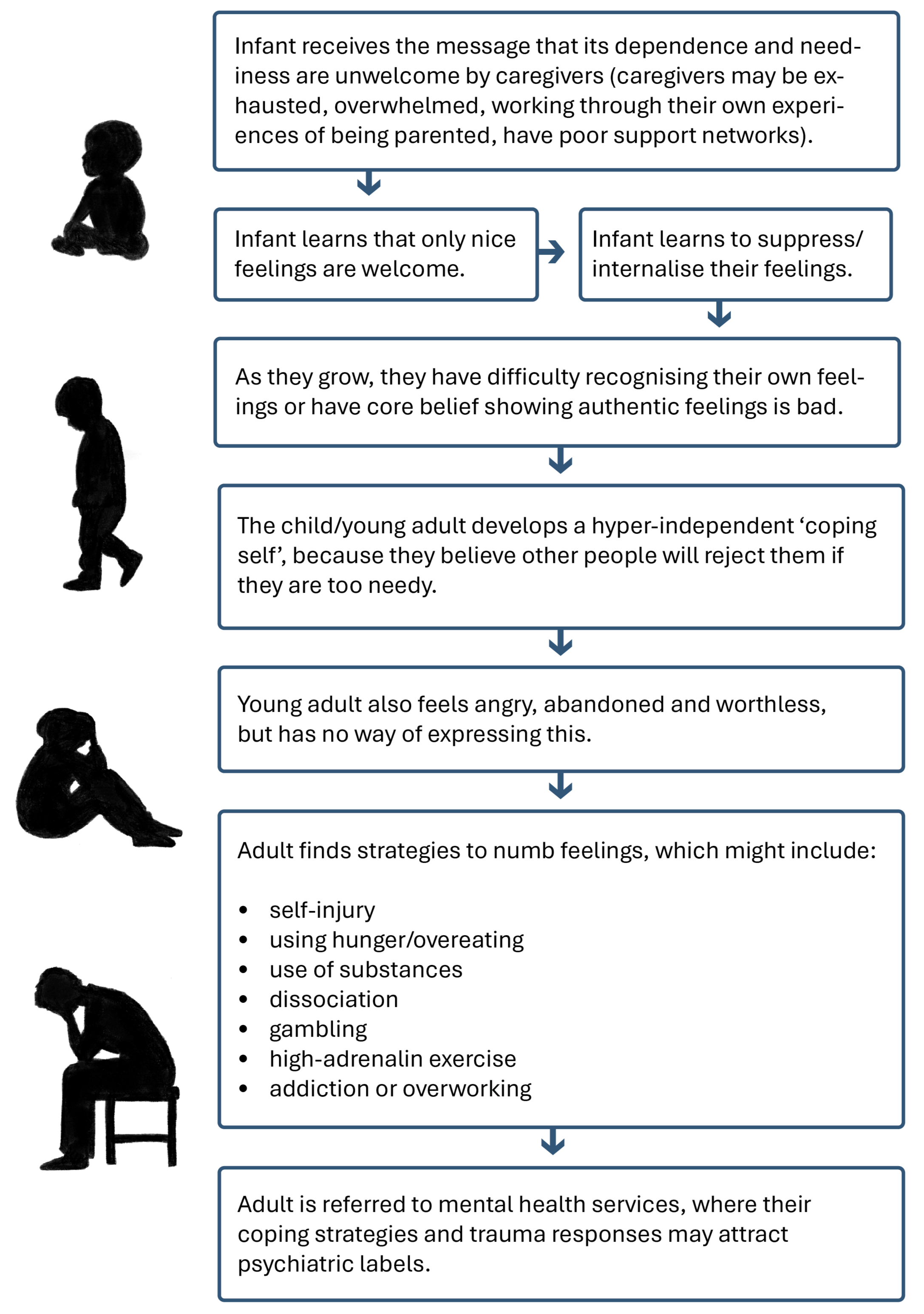

Our neural pathways are hence sculpted within our relationships and interactions from the womb, impacted at a cellular and genetic level. Through our life course, our view of ourselves and the world and our emotional and physiological responses are shaped by successive experiences. These protective adaptations and survival strategies focused on safety and belonging are rooted in our evolutionary history to protect us. However, at times, complex trauma can occur where these most primitive and fundamental needs of safety and connection may compete, where harm and lack of safety is experienced from a group or individuals to whom attachment, safety and belonging is needed. An example of this can be seen in figure 5 on the next page.

Figure 4 demonstrates how responses during crucial times in development shape how feelings and relationships are managed and how this impacts a person’s life. A child that is rejected or punished for showing distress may learn to internalise or disconnect from their emotions and not reach out for support. They may become hyper-independent to feel safe. However, in the perceived safety of disconnection they may feel abandoned, unloved, undeserving or as if they don’t belong. They may go on to manage these difficult feelings, without psychological safety or co-regulation from a caregiver by using other strategies to cope with overwhelming emotions. The focus in services can become diagnosis or treatment of the coping strategy without a parallel curiosity around the origin of its function for the person.

Figure 4: How Early Responses Shape Emotional Safety and Coping

Personal and Systemic Wounding

“The expectation that we can be immersed in suffering and loss daily and not be touched by it is as unrealistic as expecting to walk through water without getting wet”

In a world marked by inequalities, trauma is not simply an individualised experience but can have socio-economic, political and systemic causes, and become a collective wound that permeates communities, cultures and groups. Within mental health services, staff who may be drawn to caring roles through their own lived experience, and who connect with and witness the trauma of others, can be at risk of experiencing vicarious trauma or having their own trauma responses activated.

Those supporting others with emotional distress within the confines of organisational and resource limitations can experience moral injury (Thibodeau et al., 2023) through powerlessness, and be forced to repress their own emotional responses due to demands placed upon them and not having the time and space to take care of the impact. This has multiple repercussions which we touch on below. A common trauma response that is not so overtly recognised or acknowledged, but important to bear in mind here, is the ‘fawn response’, also known as ‘appeasement’ (Bailey et al., 2023). This can manifest as perfectionism or workaholism and can lead us to become ‘wounded healers’ (Cvetovac & Adame, 2017), with a focus on supporting others at the expense of our own healing.

Within healthcare settings experiencing organisational change, funding cuts, and increased demand, expectation and responsibility may find this manifests in toxic cultures developing behaviours that become a way of surviving, e.g. compassion fatigue, taking control through dominance, or becoming ‘toxically positive’ (Shipp & Hall, 2024) to avoid facing the pain of the underlying distress.

While systems focus on transactional processes, diagnostic pathways, risk assessments and care planning, the true essence of mental health work lies in people’s stories, their lives, and relationships. There can be profound connections within these relationships that can hold a space for recovery but often coexist with the trauma of witnessing suffering. It is essential to recognise and tend to this with compassionate work settings otherwise staff defences against pain may be to disconnect from people using services as humans and be unable to sit with suffering. Compassion involves being able to sit with pain rather than push it away - when compassion is lost, hurt people can inadvertently hurt others, which creates re-traumatisation.

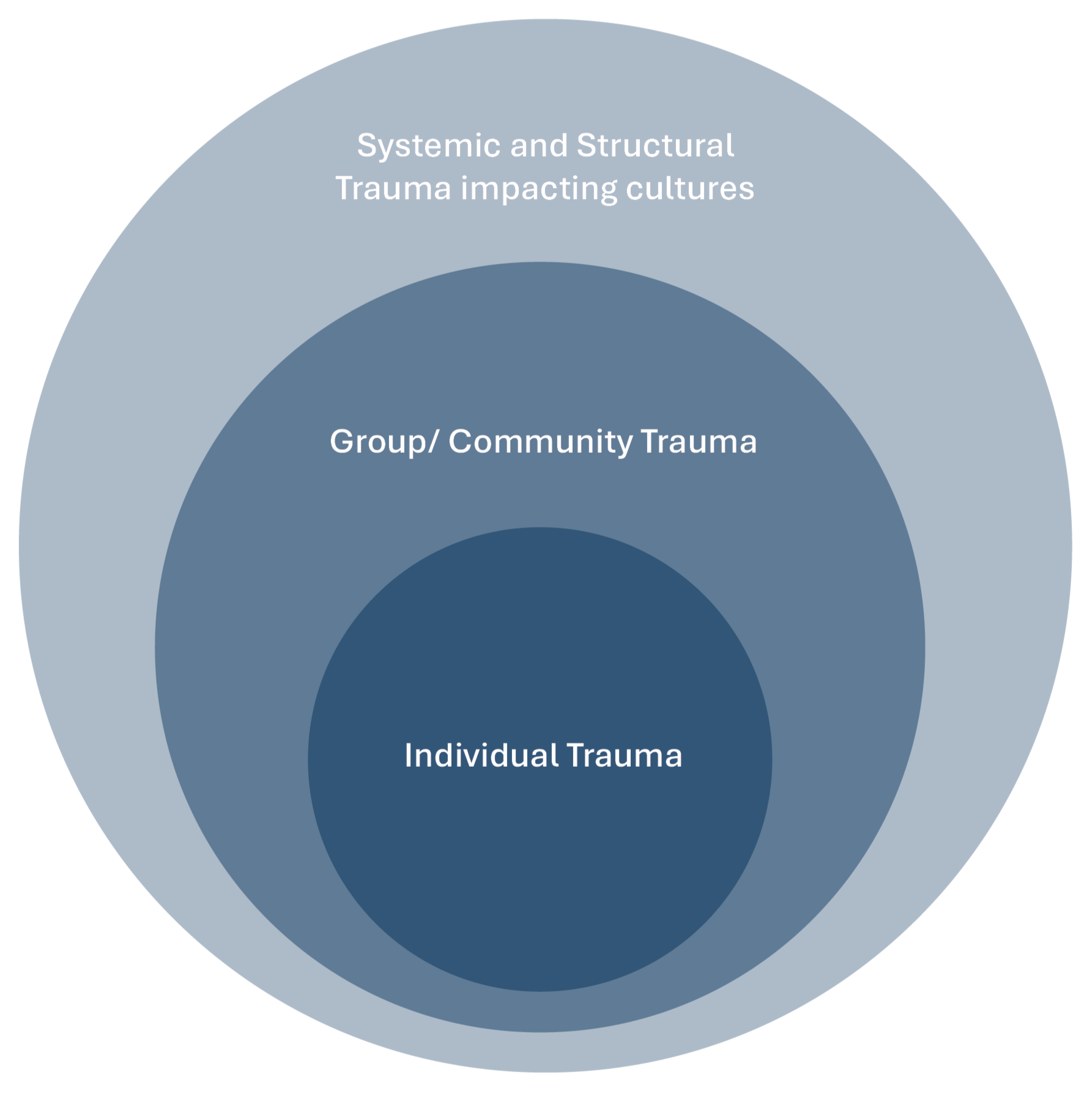

Trauma can also be felt in groups and communities, across cultures, with multiple additional stressors that disempower, alienate or silence people so they do not feel safe to be in the world as their authentic selves and become marginalised; consider Black Lives Matter, LGBTQI+, refugees etc. Personal trauma often intersects with systemic trauma, creating a complex tapestry of suffering that is both deeply personal and widely shared. It is not just an isolated experience but entwined with the socio-political fabric of our lives. Societal structures impact on individual well-being and systemic issues such as poverty, racism and injustice can lead to significant psychological wounding.

There is therefore a need to understand trauma within a broader context of enduring patterns of pain and disconnection that transcend the individual (see figure 4). Our safety and belonging are rooted in our evolutionary history to protect us. However, at times, complex trauma can occur where these most primitive and fundamental needs of safety and connection may compete, where harm and lack of safety is experienced from a group or individuals to whom attachment, safety and belonging is needed.

“The trauma of structural racism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, capitalism, poverty, ableism and all the many oppressions, could be called continuous systemic and structural trauma” (Fannen, 2021, p. 247), and could be said to be a result of colonisation.

Figure 5: Positioning individual trauma in the wider community/systemic and cultural context

Recognising trauma’s impacts on beliefs and survival responses

Trauma can impact in many ways, including but not exclusive to:

An overloaded sensory system (nervous system overwhelm)

Cognitive impacts such as poor memory and concentration

Effects on attachment development and relationships

Poor self-regard and identity development

Difficulty recognising and regulating emotions

Dissociation (disconnection from oneself or consensus reality)

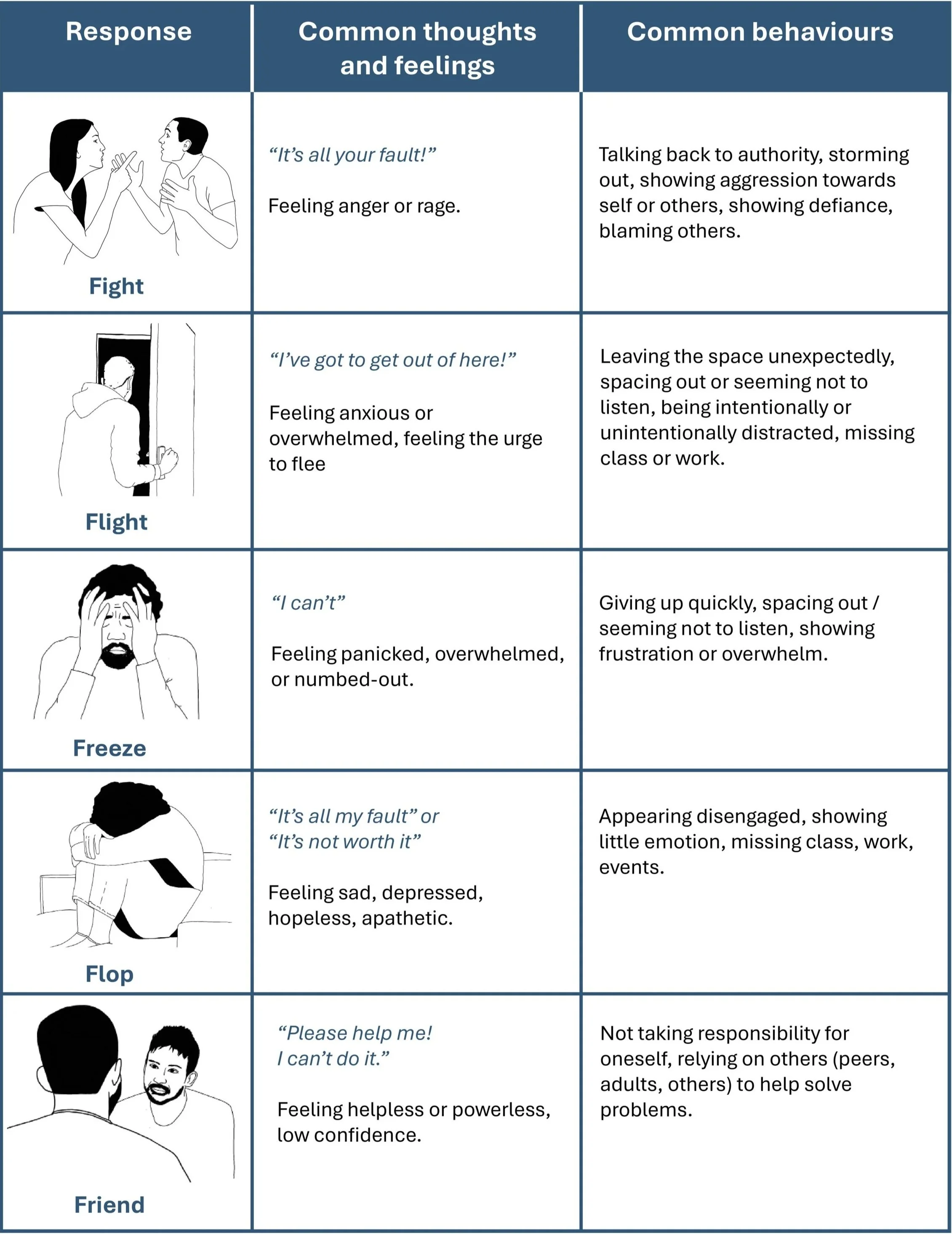

The resulting behaviours can be understood within the categories of trauma responses in figure 6.

Figure 6: Trauma responses categories example

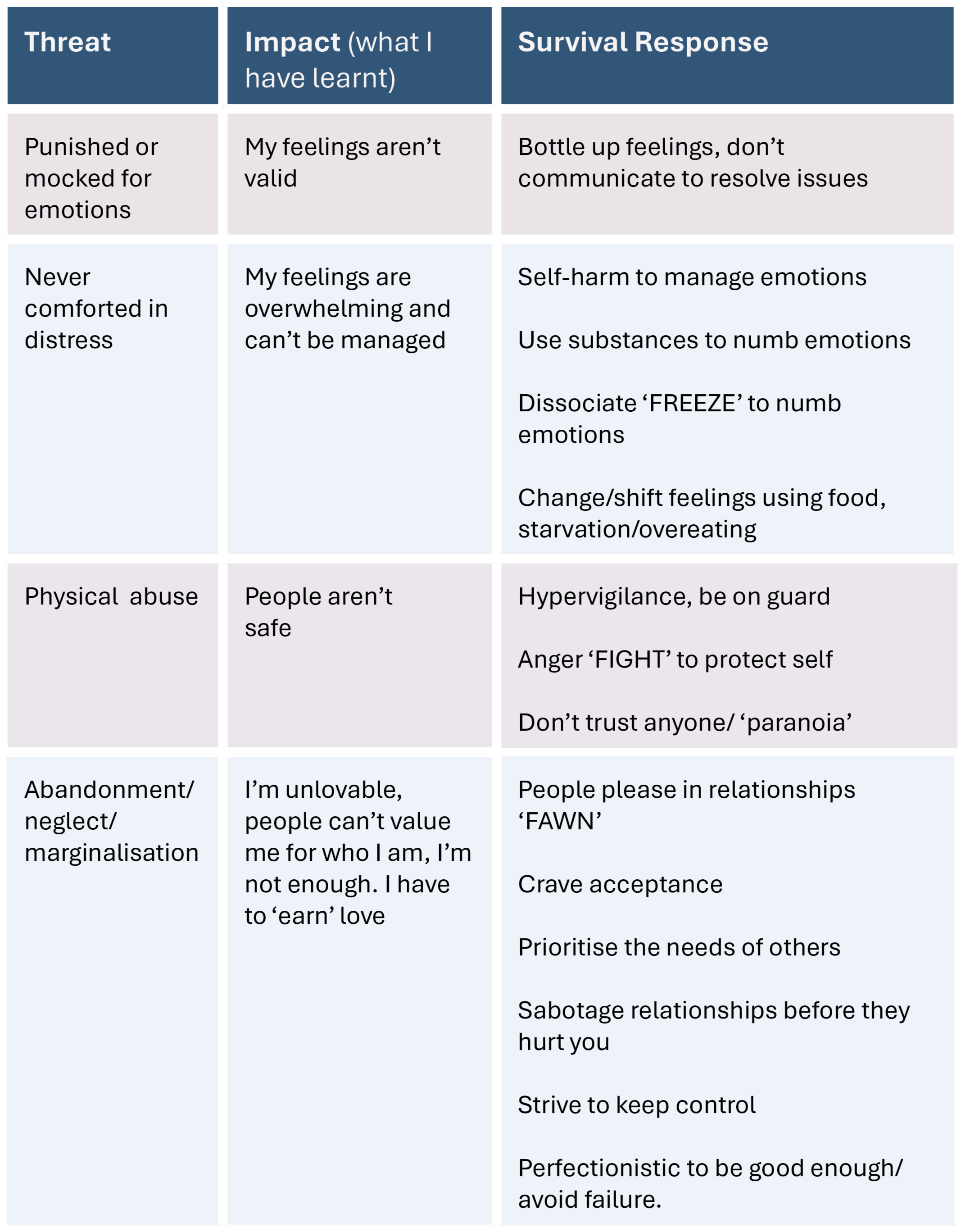

Examples of these trauma responses can be seen in table 1 (below), which highlights some possible root causes (threats), resulting beliefs (impact) and the corresponding response.

Table 1: Trauma Responses; threat, impact and response

Table 1: Trauma Responses; threat, impact and response

Table 1: Trauma Responses; threat, impact and response

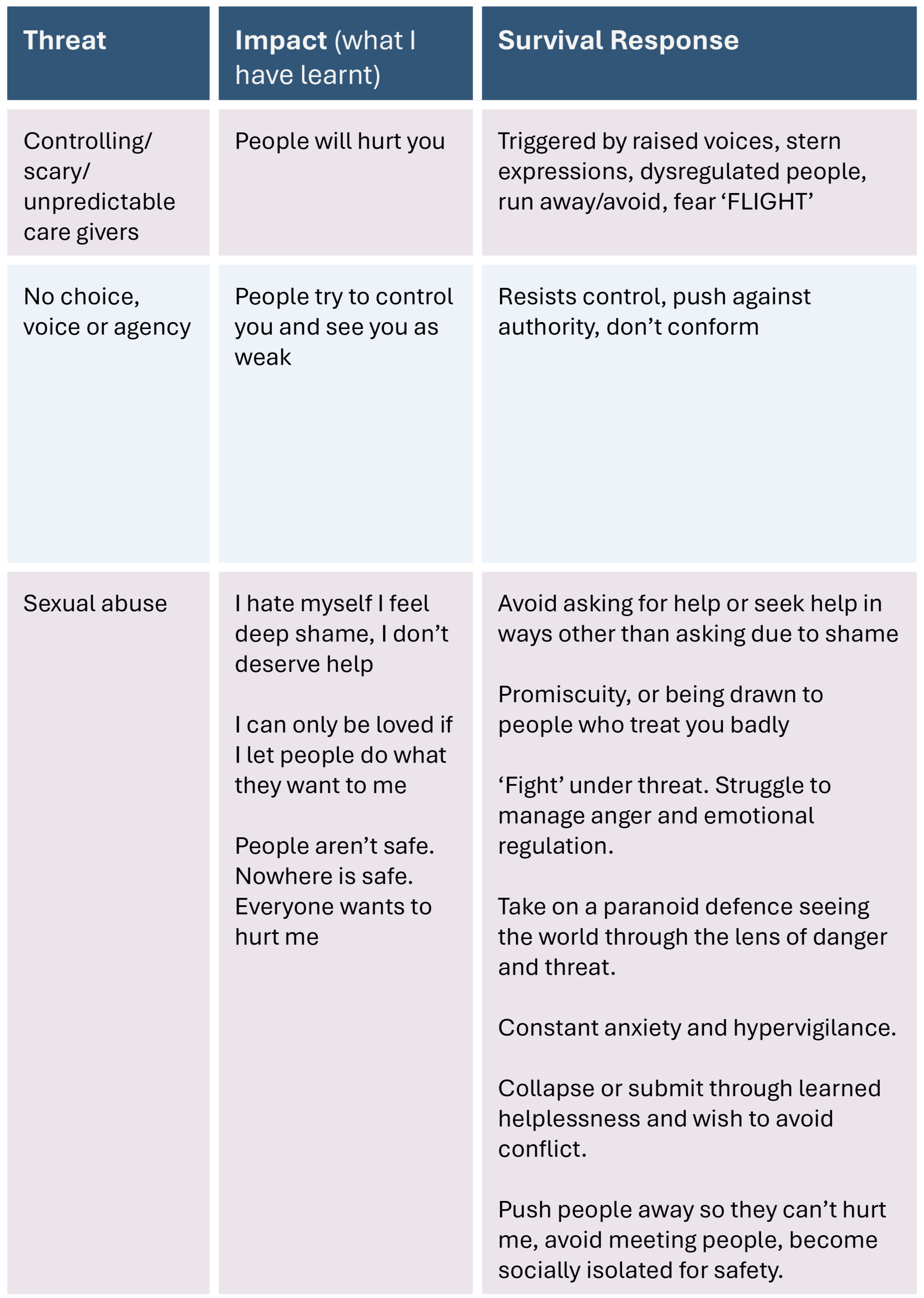

Recognising when people are outside

‘The Window of Tolerance’

We all have a ‘window of tolerance’; a range within which we can regulate and cope with stressors both emotionally and physiologically. With an accumulation of traumatic experiences, we can become hyper-sensitised to threat, in seemingly extreme ways to lesser events due to a narrowing of our own window of tolerance. A broader range of experiences are thus perceived as threats, triggering fight, flight, freeze, flop responses (see figure 7). Supporting people within trauma informed systems requires us to recognise this, and focus attention on safety and connection, rather than seeing ‘extreme’ emotional expression as a symptom of something being wrong with the person.

Fight, flight, freeze, flop and friend/ fawn can all be considered as adaptive survival responses to face, flee or avoid threat. Another not uncommon response to perceived threat or overwhelm, particularly where there is little scope to fight or flee is to dissociate. ‘Dissociation is the essence of trauma’ (Van de Kolk, 2014, p. 66). Dissociation causes a disconnect between a person’s thoughts, memories, feelings and identity enabling them to tolerate the unbearable. This can take a variety of forms ranging from feeling disconnected or ‘zoned out’ to paranoid or hallucinatory experiences, or episodes of amnesia for disconnected parts of self as might be seen in dissociative disorders. Dissociation can allow separation from parts of self that contain fear and pain and hold them, protecting them from being realised by the person.

When we consider the window of tolerance as something which describes every human being’s coping systems, it is not difficult to see how staff who are constantly exposed to caring for people in heightened emotional states, working long shifts within stretched systems can also be pushed outside of their own ranges of comfortable regulation. They themselves may feel powerless, lack a voice or feel threatened through holding risk with fear of blame.

The “Window of Tolerance” Maintaining Optimal Arousal

Figure 7: Window of Tolerance. Adapted by Imroc from the original concept developed by Dr Dan Siegel (1999).

This can then cause a cascade of interpersonal trigger responses, sometimes leading to staff disassociating from the person they are caring for and their distress in order to cope. During such times, staff can be seen to behave with a lack of compassion or even irritation, and project blame onto the person they are supporting – these reactions are ultimately also trauma responses. Research suggests that the systems in which people work in or go to receive care can replicate harms that have previously been experienced and can even be resonant of their original trauma (Reddy, & Spaulding, 2010). As previously highlighted, staff who are aware of these impacts can then experience shame and guilt due to operating outside of their own moral and ethical values (‘moral injury’) (Thibodeau et al., 2023).

It is therefore vital that staff are given the opportunity to tend to their own nervous system regulation and see this as important as tending to the distress of others. It is only through realising that we all have the capacity to provide support when we are resourced, or potentially cause harm when we are outside of our own window of tolerance, that we can recognise how we are responding. Imroc are piloting an approach called ‘Tending Distress’, introducing somatic practice to tend to our own distress when supporting others.

Recognising Trauma in Organisations

Many of the signs we see in traumatised organisations mirror those we see in individuals but are experienced collectively and can come out of unprocessed past events. Constant staffing change, feeling disempowered or losing trust in the system that doesn’t live up to its stated values.

“I can’t believe what you say,

because I see what you do”

Organisational trauma can result from emotionally draining work combined with a lack of time for reflective space or focus on wellbeing, and can come from working in under-resourced systems with high expectations and levels of responsibility.

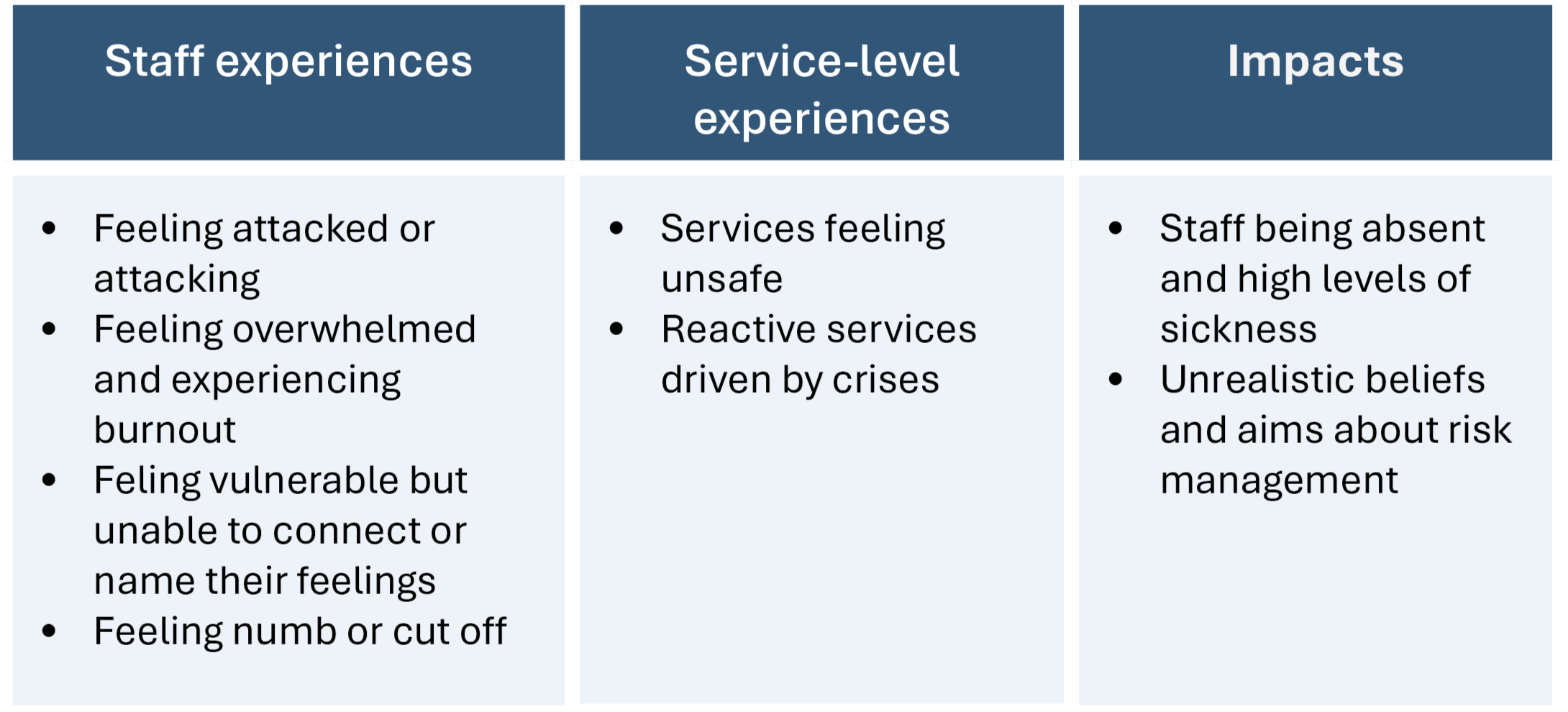

How this might be expressed can be seen in Table 2 below.

Table 2: Recognising Trauma in Organisations

Responding

So far, we have described the many different experiences that might constitute trauma, exploring the impact that they can have on biological, social and systemic levels. The prevalence of trauma is much higher than we might be aware of, and our support services are not often set up to recognise and help individuals work through their trauma responses/experiences. In fact, sometimes the services that we turn to for support might compound an individual’s trauma by removing personal control and pathologising their experiences. It is sometimes difficult to know how we as individuals can begin to change this, especially if we are working in systems which may not feel supportive of change. In the following sections, we will describe how we can respond to and support individuals by infusing trauma-responsive knowledge into practice, language, culture, policies and procedures.

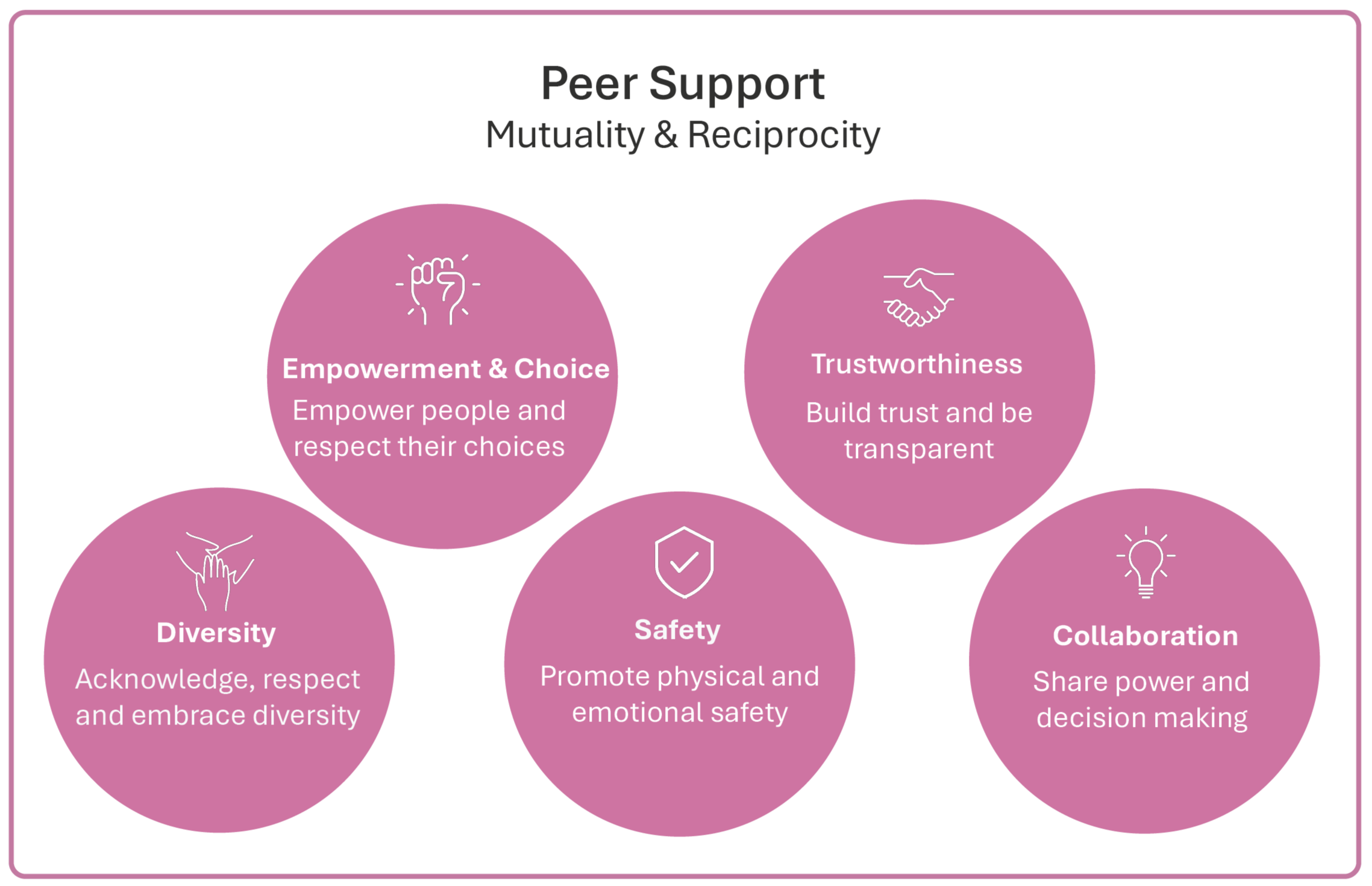

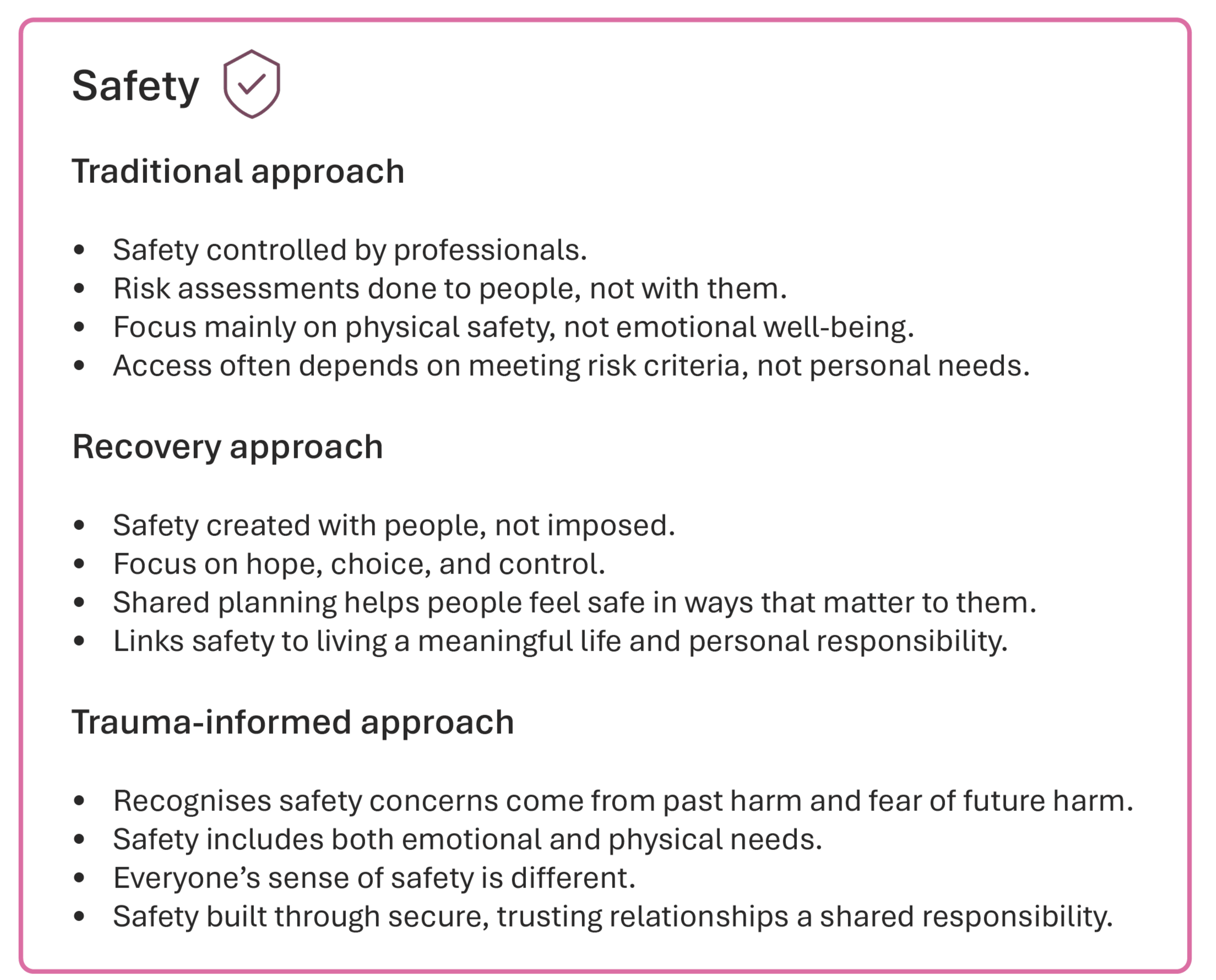

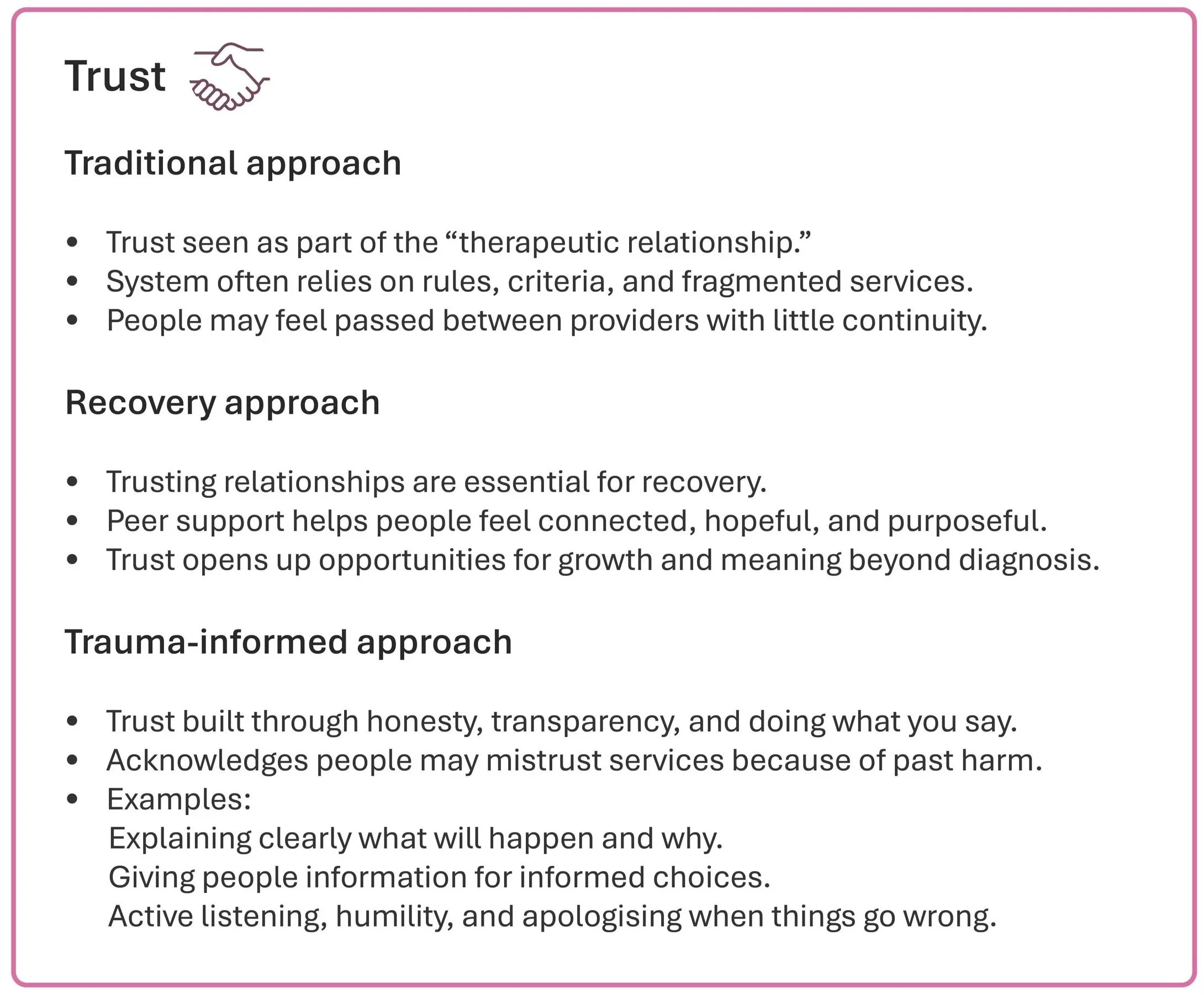

Figure 8: The principles of trauma-informed care

A comparison of different system approaches to the trauma-informed principles can be seen in the next few pages (recognising that these are not entirely discreet, and overlap exists between approaches). The traditional approach remains dominant in most Western mental health services at present.

Table 3: a comparison of the different approaches to supporting people who have experienced trauma

Responding by supporting others to heal trauma - a relational approach

Peter Levine, an American Psychologist and Psychotherapist with expertise in trauma resulting from his own lived experience, speaks to the centrality of relationships in healing trauma (Levine, 1997). In agreement with Gabor Maté referred to earlier, Levine describes developmental trauma occurring due to the absence of secure attachments and responsiveness to emotional distress, describing trauma as ‘what happens in the absence of an empathic witness’ (Levine, 1997). So, we can take this as a starting point; to recognise that an ‘empathic witness’ is necessary for those who have experienced trauma as it reduces feeling isolated in holding one’s pain.

Approaches to healing trauma, at both individual and collective levels, require us to move away from a hyper-individualised perspective (seeing the issue as residing solely within the person) towards considering the individual as part of a wider system within which their trauma was caused (Fannen, 2021; Maté & Maté, 2022; Olson et al., 2014), and in which it can be healed.

The leadership required to enable trauma-informed, recovery-oriented environments must itself be trauma-informed, understanding how unresolved trauma impacts not just the individual, but the whole organisation. Solutions are fundamentally relational rather than managerial (Cockersell & Marshall, 2024).

“It’s the relationship that heals,

the relationship that heals,

the relationship that heals”

In 2000, a team of American psychologists, led by Shelley Taylor, proposed a new response to trauma, which they termed “tend and befriend” (Taylor, 2012). Taylor described how, in times of distress, people are more likely to engage in nurturing and relationship building behaviours. These responses are underpinned by our neurobiology, through the release of the hormone oxytocin, associated with empathy, bonding and trust. The theory offers an alternative to understanding trauma responses simply in terms of flight/fight/freeze. It also mirrors results from a study by Roennfeldt et al. (2024), which explored the wished for responses from the perspective of people who had experienced trauma and accessed crisis services.

They found that recipients felt the need for responses that gave:

A felt and embodied sense of their own safety, influenced by a human to human connection

Emotional validation and holding, including being deeply listened to

A place of safety and choice within holistic care

For such responses to be possible, participants identified organising principles, including:

Recognising crises as meaningful and part of our shared human experience

Responses to crises being a community-wide issue

These principles further highlight the inextricable nature of the individual, their environment and relationships. We will explore each principle below, with a focus on how we might respond to, and support someone, in ways that align with these trauma informed principles.

An embodied sense of safety, influenced by human-to-human connection

In order to ‘tend and befriend’ in an embodied and relational way to a person experiencing a trauma response, first and foremost two things must be acknowledged:

Recognition that the person experiencing a trauma-response may have a narrowed window of tolerance, making it more likely that they find their threat system activated (i.e. they easily become frightened, angry, withdraw or shut down), and may be unable to access their rational thinking, problem solving mind until their nervous system has returned to a regulated state.

Recognition that we as supporters are not separate from the distressed person, but our own emotional and physiological reaction to their distress will have a direct impact on their experience.

Humans are relational beings and are hard-wired to seek safe connection due to our attachment needs (Fannen, 2021; Maté & Maté, 2022). Therefore, if we are able to shift our interventions to focus on ‘being with’ people, through offering a calm and embodied sense of co-regulation and thus a sense of safety, then the cycle of dysregulation can be broken as the threat is no longer perceived to be present (Plett, 2020; Porges & Dana, 2018).

This is contradictory to the expectations often put on professionals to assess or have an ‘intellectual resolution’ to the problem within a transactional rather than a relational process. The tendency of services to expect staff to live in their heads and over-intellectualise responses, rather than promoting an embodied way of being with people, can actually prevent the healing outcome hoping to be achieved.

It is vital to remember that a person who has experienced trauma can become hypervigilant to perceived threat in others and can misinterpret neutral cues as threats. As supporters, therefore, we need to ensure that we are offering a gentle and compassionate space in order to minimise any perceived threat.

This can be extremely challenging to maintain, as facing someone in a distressed state is likely to activate a threat response in our own nervous system. If we as supporters are able to stay within our own window of tolerance, we are more likely to attune to the person we are supporting and have a calming influence. This requires us to have done (or be actively doing) our own trauma healing.

“Attunement can be simply defined as the focus of attention on the inner world. Interpersonal attunement is the focusing of kind attention on the internal subjective experience of another”

This is why trauma informed systems must recognise us all - the people being supported and the people offering support alike - as equal humans that can all be impacted in these ways. It is only when supporters have sufficient capacity to self-regulate, that they are able to support another person in feeling safe. It is much easier to offer a healing relationship to others if we are actively engaged in our own embodied healing as we have some understanding of the situations which might draw out our own trauma responses, and what we might be able to do in those circumstances to stay regulated. “If we want to foster change in our organisational behaviour…equally important is to promote self-reflection in the workforce, to understand our own emotions, needs, triggers and motivations” (Skeate & Templeton, in Cockersell & Marshall, 2024, p.69)

Responding through validation and emotional ‘holding’, including deep listening

The more we can sit with our own emotions in an embodied way as a supporter, the more we are able to offer a depth of support and validation for others without our own reactions getting in the way or causing us to want to shut down the emotional expression of another. This approach is often referred to as ‘holding space’ for another. Holding space can be seen as acting as a temporary container for someone’s pain when they are unable to hold it for themselves – they may be experiencing extreme emotions in reaction to a traumatic life event and temporarily feel ‘broken’ – we don’t see their brokenness as something wrong with them which needs to be pushed aside or resolved, but instead we hold their brokenness with gentle compassion. We help them to see that they are not alone…we give them boundaries, so they are protected from further hurts. We give them a listening space for the waiting they must do whilst their nervous system regulates (Plett, 2020).

Honouring healthy boundaries and an equal focus on inward self-care is a necessary priority for us to offer a safe space to others. Normalising emotional reactions and reframing threat responses as natural, transient reactions to adverse life experience are proven to have a positive impact in clinical practice (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018).

“Knowing you are not alone and having validation is an important stepping stone towards positive transformation”

Open Dialogue is a compassionate approach to mental health care that originated in Finland in the 1980s, and offers a powerful example of a trauma informed approach. It emphasises recovery through open conversations, acknowledging the connection between the individual and their social network (Olson et al., 2014).

Key principles of the Open Dialogue approach are its emphasis on:

the importance of every voice in the space - that the answer to the problem lies between people rather than within an ‘expert’

the tolerance of uncertainty - acknowledging the paradox of letting go of the need to find a ‘solution’ to the expressed pain may be the gateway to a resolution arising naturally.

Peace activist Marshall Rosenberg recognised the power of language and developed a form of ‘nonviolent communication’ (NVC) which emphasises empathetic listening, unconditional positive regard and authenticity in a supportive therapeutic relationship (Azgin, 2018). The ability to deeply listen to another without allowing our own emotional response to taint our perception of what we hear takes a great deal of self-awareness and skill (Plett, 2020). We are able to offer relational safety through holding an astute self-awareness of our own emotional responses rather than numbing them down, and from that place can ‘be alongside’ another with a sense of curiosity and exploration rather than a preconceived judgement about what might be going on for them.

By showing up authentically and giving something of ourselves, we can start to flatten any sense of hierarchy. A powerful approach to holding space to deeply listen starts with becoming curious, wondering; “What’s the story behind the presenting behaviour?”

“It seems counterintuitive, but the way to truly be helpful to someone in pain is to let them have their pain. Let them share the reality of how much this hurts, how hard this is, without jumping in to clean it up, make it smaller, or make it go away.”

Emotional arousal can indeed be an important messenger broadcasting the presence of an unmet need which can lead to deeper understanding and growth. In this way, a crisis can be viewed as a potential opportunity for change and healing, if correctly supported.

It is a much more compassionate approach when we stop hyper-individualising pain and see it through a curious lens - trauma and distress happen between people - if we are able to step away and regulate our own physiological response in any situation, we are more able to objectively see that all parties are feeling challenged.

It is important to recognise that there are stages of healing trauma, and if we jump to trying to be compassionate to others before ourselves, then we are at risk of bypassing a necessary stage of our own nervous system regulation, which can unintentionally cause further distress to those we are intending to support. Self-reflection is key: when supporting others in distress, do we fall into a fight/flight/freeze/fawn response, or are we able to stay within our own window of tolerance and therefore offer a healthy level of co-regulation via a calming presence?

Responding with a place of safety and choice within holistic care

Safety ultimately means an absence of threat or disempowerment (Johnstone & Boyle, 2018), and this can be both emotional and/or physical. Fannen (2021) highlights that safety also involves reclaiming a sense of physical agency in our lives, and the ability to address and change the thing that caused the trauma (Herman,1992). This inextricably links an individual’s wounding to their social network and wider environment, and the fact that different people will have differing levels of autonomy within the physical spaces in which they exist. It is therefore vital that the people we support have the agency to create a physical space that feels conducive to their own healing journey. Safety (relational, psychological and physical) is the first task of recovery and is a necessary foundation for deeper therapeutic work.

As a foundation, this includes:

Having access to a warm, comfortable shelter, away from the cause of trauma

Having the freedom to move around whenever necessary, e.g. connecting with nature to ground or exert excess energy, and never feeling ‘trapped’ within an environment.

Being respected to self-isolate or create a safe ‘cocoon’ to retreat to

Having holistic healthy food options to support nervous system regulation

Having access to ways of expressing thoughts or feelings non-verbally, such as with art materials or musical instruments

Being able to connect with others who are able to offer platonic physical touch (e.g. a hug) if that is invited / welcomed.

For a healing environment to offer physical safety, all of the above elements must be considered.

Research shows that incorporating trauma-informed principles in mental health wards can improve the outcomes for people using services (Baker & Wong, 2019; Sweeney et al., 2016).

Studies have focused on the importance of:

Reducing the use of restraints and seclusion.

Creating a calm and supportive environment that is sensitive to the needs of trauma survivors.

Training staff to understand the impact of trauma on behaviour and emotional responses.

Recognising the role of past trauma in people with mental health diagnoses

Some studies suggest that implementing trauma informed care can lead to a decrease in the use of psychiatric medications, fewer incidents of aggression or self-harm, and improved relationships between people using services and staff. If it is done well, the relationally enabling environment of a [trauma informed] therapeutic community becomes the ‘treatment’ itself (Haigh, 2013, as cited in Cockersell & Marshall, 2024).

Responding with a trauma-informed approach to supporting people in crisis

Knowing how best to hold space for someone in distress requires us to understand how each trauma response (highlighted in figure 6) - fight, flight, or freeze/flop - requires a specific approach to help individuals move back toward their window of tolerance and a sense of safety and regulation.

For example, when anger and frustration are being expressed, this indicates a state of hyperarousal aligned with the fight response.

Helpful responses can be:

Acknowledging the emotional expression as valid to help the person feel seen and understood.

Encouraging physical activities to discharge excess energy, such as running or punching soft objects.

Offering alternative ways of expressing the intense feelings (as verbal communication may not be possible), such as creativity - painting or modelling with clay etc

Emphasising choice and control: Feeling in control can be essential when someone is scared, fear is always underneath anger, and so avoiding power struggles, and providing options wherever possible is key.

Restlessness, hyperactivity, anxiety, overwhelm or seeming ‘paranoid’ are also expressions of a state of hyperarousal, but more aligned with a flight or flee response.

Helpful responses can be:

Reassuring the person of their safety in the present moment with you - say it overtly; “[say their name] you are safe now” repeatedly if necessary

A sense of physical safety may be supported by feeling gently contained, e.g. being wrapped in a heavy blanket (with overt permission from the person)

Encourage gentle movement: stretching or rolling on the ground or walking if it helps to discharge the anxiety.

Followed by: Simple grounding techniques like focusing on breathing or feeling their bare feet on the earth to regulate the heart rate

Offering a routine and structure: a predictable routine can provide a sense of security through familiarity, counteracting the urge to run away.

Experiencing a freeze / flop response can manifest as feeling stuck, numb, dissociated, or disconnected. The individual may feel emotionally shut down, or even become mute or catatonic.

Helpful responses can be:

Encouraging gradual re-engagement with sensations (like holding something textured or using temperature changes) can help reconnect the person with their body.

Creating a safe, calm environment by offering reassurance without pressure to engage - ‘being with’ the person and respecting their need for silence or stillness.

Gently guiding their attention to safe, present-moment details in the room (sounds, sights) can reduce dissociation.

Encouraging tiny movements through gently suggesting wiggling of fingers or toes, can help them slowly regain a sense of agency and control in their own body.

A very gradual titration of re-embodiment and co-regulation may be necessary due to fears that may instinctively arise when reconnecting with the body, so any guidance requires discernment and a gentle approach.

Figure 9 on the next page shows simple steps in how we can support someone who is in a heightened emotional state.

Figure 9: how we can support someone who is in a heightened emotional state.

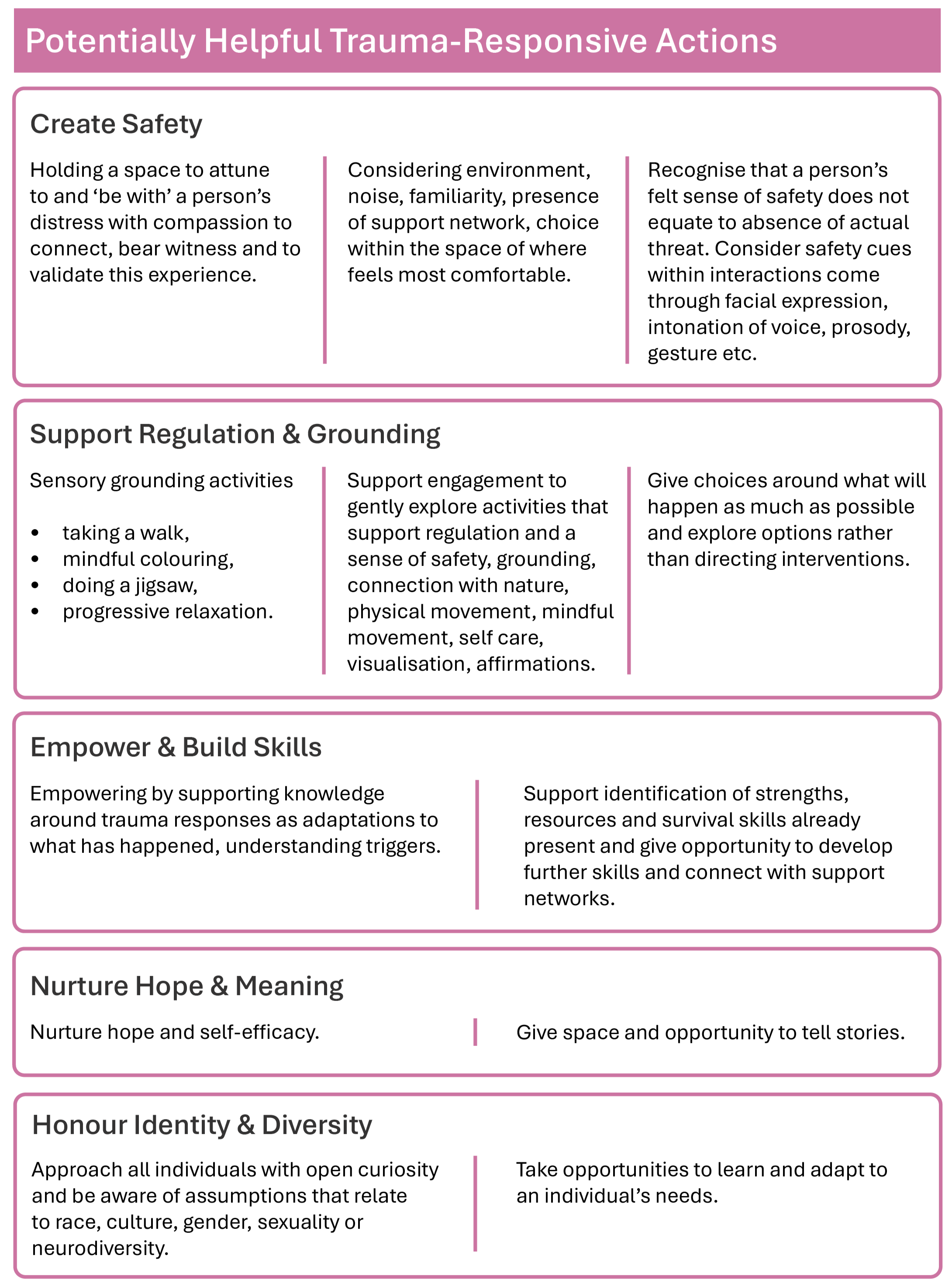

Table 4 provides a summary of potentially helpful trauma responsive actions.

Resisting

Resisting Re-traumatisation

It is fundamental that within a trauma informed system we recognise the capacity we have to unintentionally traumatise people through the systems and processes we have in place. If we are to prevent the re-traumatisation of the individuals we support, we must recognise that trauma does not separate us – it affects every one of us at varying degrees.

It is important to recognise that, because trauma invariably comes from being disempowered, (things happening beyond your control for which there was no choice or sense of agency within, and where you may have not been seen, heard or believed), we have the potential within services to re-enact patterns through our language, our practices or our way of being with each other and with the people who access our services.

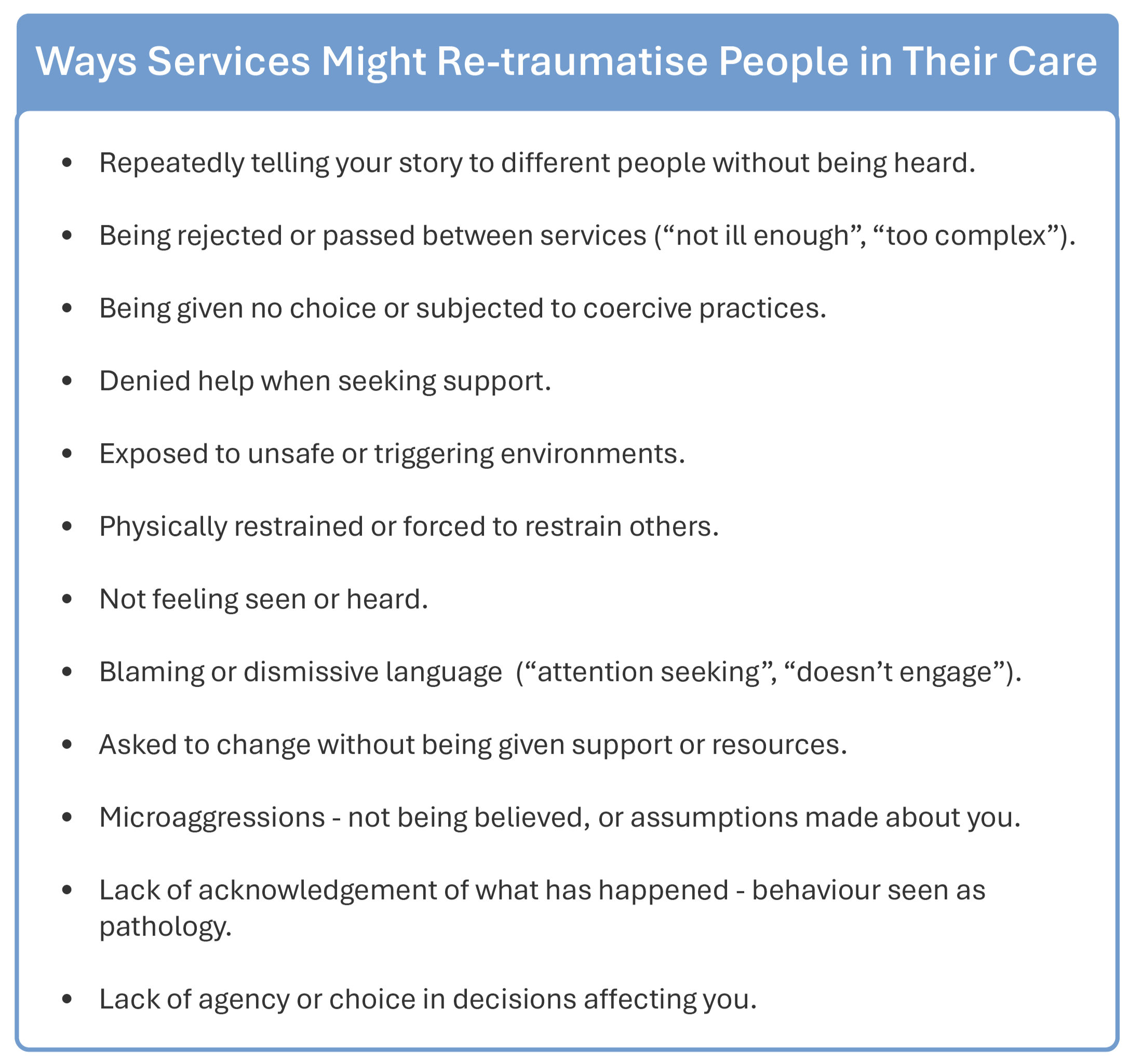

The next page highlights examples of ways re-traumatising can happen in services (applies to staff and people using services).

Table 5: examples of ways that services might re-traumatise a person in their care

Recognising the impact of clinical interventions and environments in terms of the potential to trigger distress and cause additional trauma is a positive step to resisting re-traumatisation.

Trauma informed services resist practices that cause further disempowerment or re-traumatisation.

Some ways in which they do this is by:

Prioritising a person’s sense of safety – emotional, physical and relational (not just actual safety or addressing the anxiety of services through risk assessing)

Utilising holistic adaptive approaches that recognise the unique needs of the individual as a human being (not dictated by diagnosis or blanket policies)

Using language that is non-pathologising, blaming or shaming (Language is powerful and may echo the criticisms and traumatic invalidation people have experienced in their past)

Understanding experiences and behaviours as wise responses in the context of a person’s story, and

Being curious about that story and supporting them to recognise and own it.

“Owning our story and loving ourselves through the process is the bravest thing that we will ever do ”

Resisting re-traumatisation through recognising crisis as meaningful and part of our shared human experience

A trauma informed approach also honours the possibility that strength can be gained through adversity with the right support. This opens the potential for trauma to be overcome, even acting as a catalyst for growth and positive transformation over time, if external circumstances allow. ‘Post-Traumatic Growth’ (PTG) acknowledges that the struggle with highly challenging life events can lead to significant positive change (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1995).

Having the freedom to make meaning from experiences in a way that feels significant for each individual, makes way for PTG due to its re-empowering impact. The study: Evaluating Positive Changes in Psychosis (EPOCH) (Ng et al., 2021), aimed to develop knowledge into how PTG occurs for individuals following experiences that had been diagnosed as psychosis.

Results identified that mediators of PTG included those impacted having found:

a meaning in life

a change in their core beliefs

a positive reframing of their experience

a personal identity and perspective shift due to the experience

These findings align with the three pillars of recovery: Hope, Control and Opportunity (early Imroc Recovery papers about this can be found here).

It is widely recognised that hearing stories of other people overcoming adversity can be helpful. Sharing the recovery stories of others (and our own if it feels safe to do so) can be a powerful way of offering the people we support options about the stories that they may tell about themselves. Databases of recovery stories now exist and have been found to support people to feel part of a community (Slade et al., 2024).

“For those of us who have been diagnosed with mental illness, hope is not just a feel-good emotion -

it is a lifeline.”

Story sharing is a means to increased human connection and dismantling hierarchies, recognising human pain as a shared experience, whatever our social status. Evidence also shows that offering peer support to others following PTG facilitates meaning and purpose in the life of an Experiencer. This validates lived experience as a genuine and necessary form of knowing (Smith-Merry, 2019) and emphasises the inter-relationality of human distress and healing.

“Peer support is breaking the stigma and normalising mental health [challenges]…saying no actually, this is reality for people, it’s connected to the story of their life, it’s connected to something that’s happened to them”

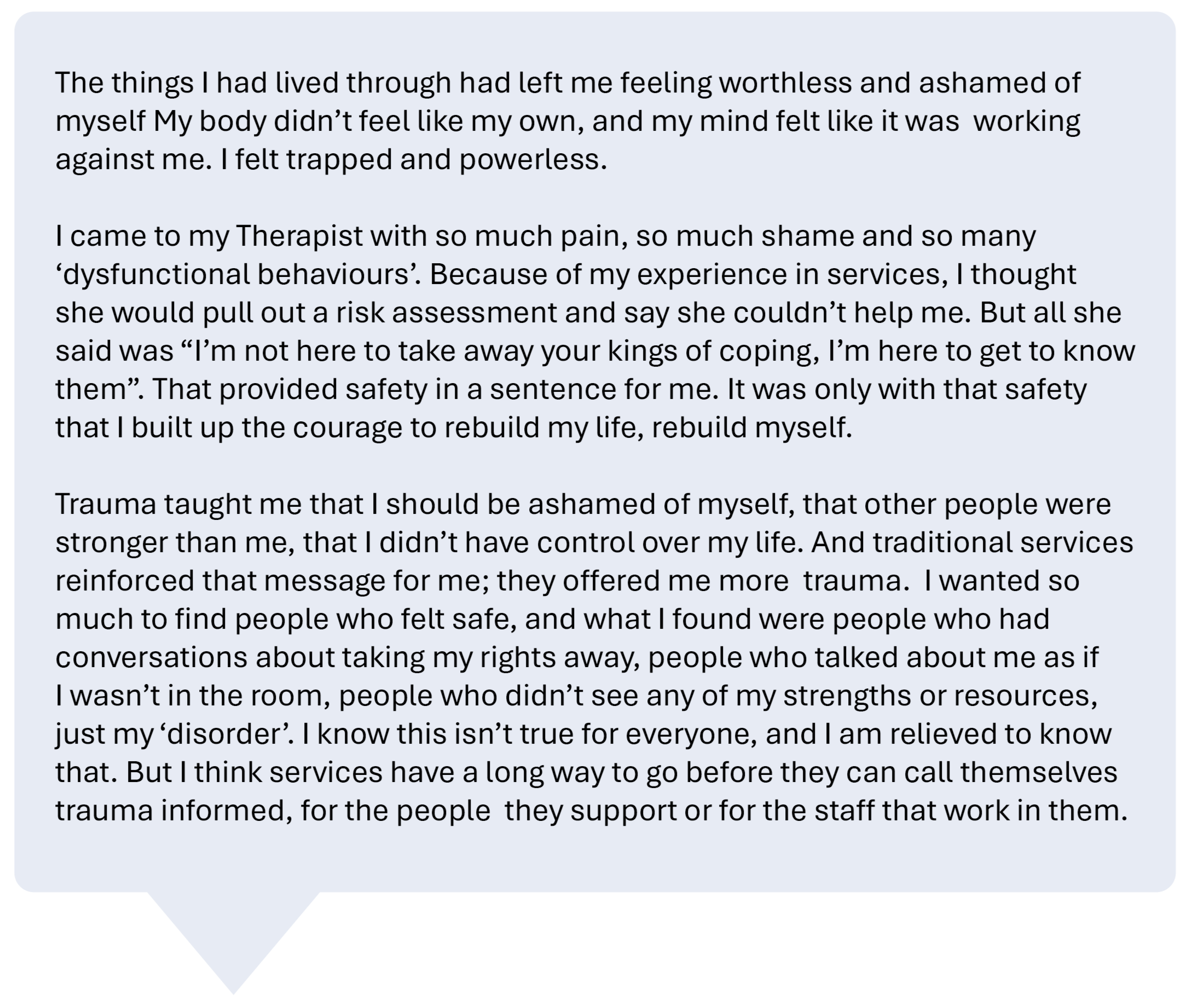

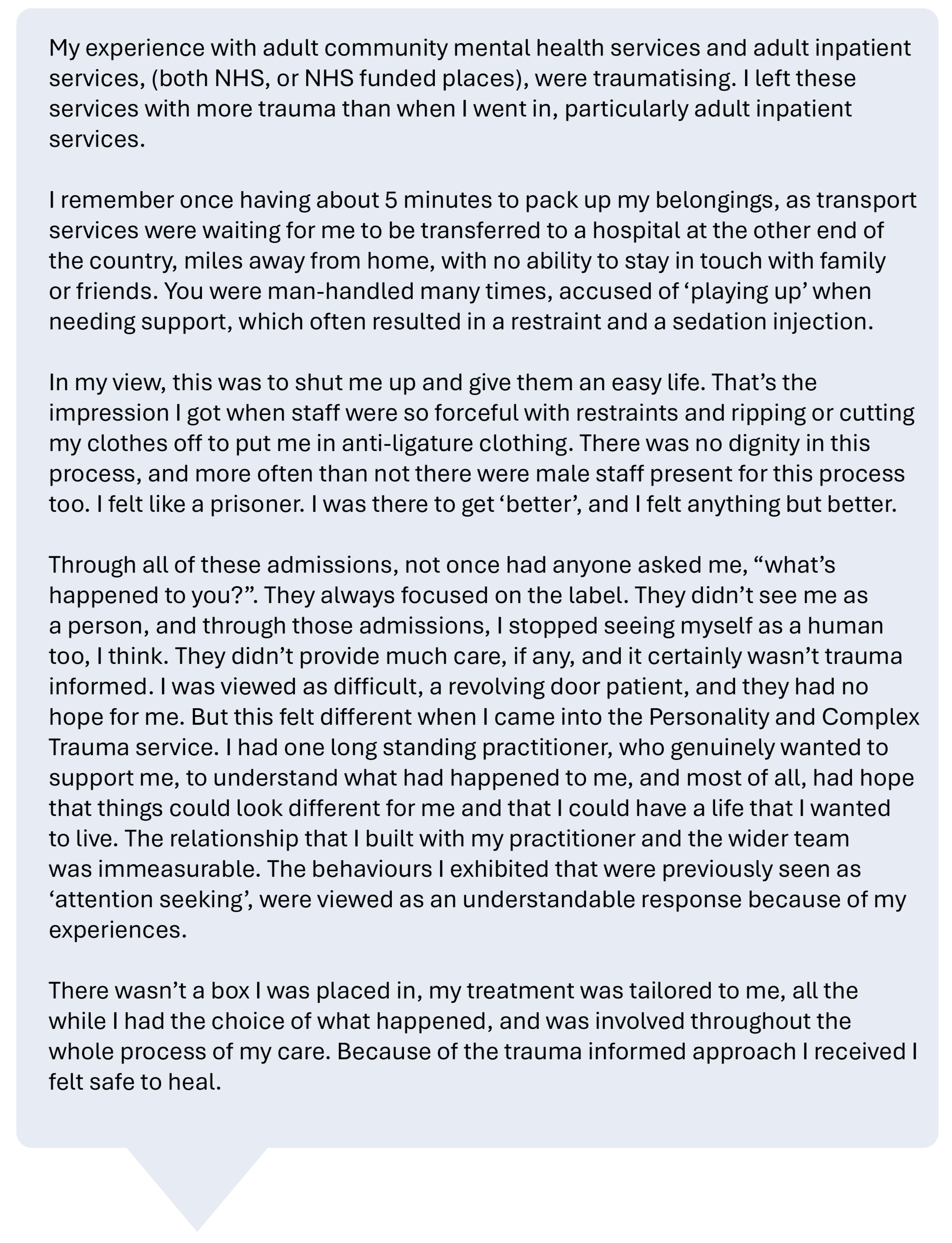

Listening and learning from the voices of lived experience – personal narratives

Lana’s story

Martha’s story

Resisting re-traumatisation through trauma informed organisational practices

Research indicates that embodiment practices can offer significant benefits to staff in mental health settings by reducing stress, enhancing emotional regulation, and improving overall well-being. These practices, such as breathwork, body scans, and mindful movement, help individuals process stress and trauma stored in the body, leading to greater emotional awareness and self-care. For example, studies on approaches like ‘Somatic Experiencing’ (Payne et al, 2015) have shown positive outcomes in managing stress and anxiety, which are common in high-pressure environments like acute mental health services. Incorporating these methods into workplace training can foster a more supportive and mindful work culture, potentially reducing burnout through increased nervous system regulation for all.

It is important to recognise that embodiment practices need to be approached very carefully as they can expose trauma that is sometimes repressed at an unconscious level.

Trauma-aware policies can help to reduce stress, compassion fatigue, and absenteeism, while fostering psychological safety and staff retention, especially in high-stress roles (Hülsheger et al., 2013). Such approaches can support emotional regulation, empathy, and communication, leading to better teamwork and client satisfaction (SAMHSA, 2014). Organisations adopting these practices report higher engagement and inclusivity, creating healthier and more sustainable workplace cultures. Berthollier et al. (2024) acknowledge that changing relationships to create a less hierarchical structure across a whole system is necessary to ensure it is therapeutically beneficial. If we can create healthier workplace cultures, then this ripples out into our wider communities, which is also a key premise of the Open Dialogue approach. This reflects the paradigm-shifting power of co-regulatory practices and attunement.

Whilst moving to more trauma informed organisations is important, there is perhaps a risk of ‘trauma’ becoming a buzz phrase - ‘Trauma informed’ has the potential to be misused by systems as part of policy to indicate something that has been achieved or completed without real, embedded change being evident at an experiential level. It is important, therefore, that we remain humble, curious, and open to personal and organisational growth, allowing a space for ongoing learning.

Central to this is holding in recognition historical power imbalances, and the necessity to value the voices of people with lived experience in shaping and driving cultural change. It is important to maintain balance so that an overuse of the term ‘trauma informed’ does not result in a dilution of its importance, key understandings, and practical application. Being trauma informed requires constant reflection and re-evaluation to become truly trauma responsive in our approach.

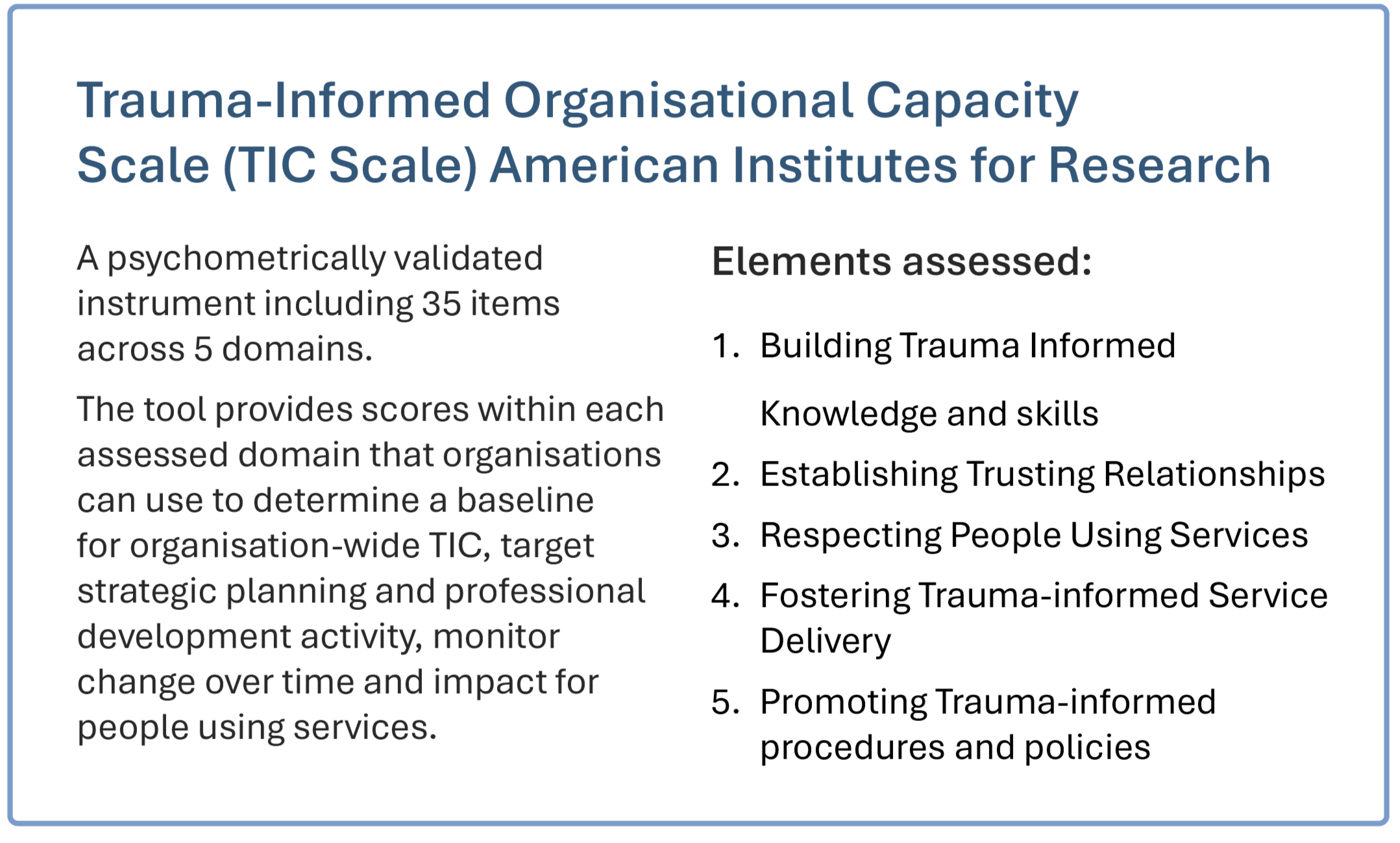

Evaluation of Trauma Informed Care

For trauma informed care to be reliably embedded within organisations it is key that capacity is built to evaluate trauma informed innovations and initiatives, and that successful initiatives are supported by overarching policies to create sustainable change.

Implementing trauma informed care needs to recognise everyone’s experiences are unique and should involve and empower people using services, carers and staff to develop approaches together within different settings.

Evaluation is essential to successful implementation and can include collecting and actively listening to feedback from people using services and staff. There are also a number of tools that can be utilised to support review and evaluation of services to help shape developments.

Some examples of how Trauma-Informed Care (TIC) is assessed across systems are shown in the three boxes below, which present tools for evaluating trauma-informed practice.

Responses to crises are a community-wide issue

Trauma informed principles highlight the vital importance of the community and wider environment when addressing trauma; both in terms of considering the potential root causes, and in the role they can play in a healing journey.

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has highlighted the role of community and social support in improving mental health outcomes in the Global South. For example, in regions like South Asia and Latin America, shifting from institutional care to community-based support has shown significant benefits. A WHO report suggests that community mental health approaches lead to better integration following a crisis, such as in initiatives like India’s Atmiyata project (“Atmiyata” means warmth or empathy in Gujarati), which trains community volunteers to provide mental health support in rural areas. Evaluations show that these initiatives have led to reductions in depression and anxiety, alongside improvements in social participation and quality of life (WHO 2022).

It is also important to acknowledge that wider cultural approaches deem emotional distress to be a wise messenger, informing the experiencer that something in their life needs to change. Some indigenous traditions say that the psyche has an inherent healing function which can manifest as behaviours that might appear outside of the social norm for western culture (Marohn, & Somé, 2014). Ubuntu is an African philosophy rooted in the idea that “I am because we are”, emphasising our interconnectedness, compassion, and collective well-being. The Ubuntu approach shifts away from individualistic, Western-centric models toward community-based healing, recognising that psychological distress is relational and requires social, cultural, and spiritual support. Johnstone and Kopua (2019) highlight that when people are distressed, the Western psychiatric model tries to find a disorder to fit the distress into, but the Māori Mahi a Atua approach instead looks for the meaning behind the distress.

“How do we indigenise our spaces to

ensure that transcultural knowledge systems

are valued and utilised?”

Trauma is a complex issue, and we are only just starting to understand the importance of embodiment, and the interconnectedness of individual, systemic and collective wounds.

Trauma healing is a process of both learning and perhaps ‘unlearning’ about ourselves, each other and the communities and cultures to which we belong.

It is important to recognise the limitations of the traditional approach to emotional distress within the Global North, and to stay curious about what we could learn from indigenous approaches.

“Madness does not reside solely in an individual,

but lives beyond and between people and is cultural”

Trauma and systems expert Thomas Hübl’s approach to collective trauma healing emphasises recognising and addressing the unconscious wounds that affect societies, communities, and cultures. He sees collective trauma as historical or intergenerational pain that remains unresolved, manifesting in ongoing social issues and patterns of disconnection. His work blends transcultural practices, embodied awareness of trauma responses, and group processes to create spaces where people can explore shared wounds, foster empathy, and reconnection. Through his work, Hübl (2023) aims to create “collective healing fields,” ultimately supporting individual and societal transformation.

Anne’s story

Conclusion

Trauma affects every living human, and paradoxically, the key to collective trauma-healing may lie, not only in providing support to others, but equally ensuring that we have prioritised our own healing in order that we are able to provide the safest and authentically caring spaces. A wealth of wisdom comes from those with lived experience who have traversed this recovery journey, and as Roennfeldt et al. (2024) attest, lived experience expertise is integral to informing a new paradigm of trauma-responsive care.

In recognising and giving witness to what people have lived through, we can also recognise and give witness to humanity’s intrinsic strengths, resilience, and survival capabilities. There is space within trauma informed approaches to recognise and celebrate our strengths and innate resources. We can also acknowledge innate pre-existing intelligence supporting survival, whilst giving potential for growth beyond what has happened, and the healing of psychological wounds. This innate resilience can also be considered beyond the individual; a collective inherited connection to life and belonging, being part of something bigger than the ‘self’.

Embracing trauma as a concept and focusing on the impact of ‘what has happened’ to people is a stark contrast to the limited acknowledgement it has been historically given. Mainstream mental health services have predominantly focused on diagnostically driven understandings that locate and aim to treat the problem within the individual. It is certainly long overdue that trauma is recognised for its significance within mental health, the impact that such recognition has on a range of social and physical outcomes, both for the individual and humanity as a whole.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our brave contributors for their invaluable narratives and to all the amazing people that continue to help us learn and understand through courageously sharing their lived experience. Our deepest gratitude also to Emma Watson, Julie Repper and Martha Barratt for their advice and guidance in supporting this publication.

-

Ashton, K., Bellis, M., & Hughes, K. (2016). Adverse childhood experiences and their association with health-harming behaviours and mental wellbeing in the Welsh adult population: A national cross-sectional survey. The Lancet, 388(Supplement 2), S21.

Azgın, B. (2018). A review on “Non-Violent Communication: A Language of Life” by Marshall B. Rosenberg. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 7(2), 759. https://doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v7i2.1550

Bailey, R., Dugard, J., Smith, S. F., & Porges, S. W. (2023). Appeasement: Replacing Stockholm syndrome as a definition of a survival strategy. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 14(1), 2161038.

Baker, L. E., & Wong, S. S. (2019). Impact of trauma-informed care on mental health service outcomes. Psychiatric Services, 70(1), 45–53.

Bellis, M.A., Lowey, H., Leckenby, N., Hughes, K. & Harrison, D. (2013). Adverse childhood experiences: retrospective study to determine their impact on adult health behaviours and health outcomes in a UK population. Journal of Public Health, 36(1): 81‐91. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdt038.

Bellis, M. A., Hughes, K., Leckenby, N., Perkins, C., & Lowey, H. (2014). National household survey of adverse childhood experiences and their relationship with resilience to health-harming behaviors in England. BMC medicine, 12, 72, 1-10.

Benjet C, Bromet E, Karam E,G., Kessler R.C.,McLaughlin K.A., Ruscio A.M., Shahly V, Stein D.J., Petukhova M, Hill E, Alonso J, Atwoli L, Bunting B, Bruffaerts R, Caldas-deAlmeida J.M., De Girolamo G, Florescu S, Gureje O, Huang Y, Lepine J.P., Kawakami N, Kovess-Masfety V, Medina -Mora M.E., Navarro-Mateau F, Piazza M, Posada-Villa J, Scott K.M., Shalev A, Slade T, Ten Have M, Torres Y, Viana M.C., Zarkov Z, Koenen K.C. (2016) The Epidemiology of traumatic event exposure worldwide: results from the World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Psychol Med. Jan;46(2):327-43.

Berthollier, N., Dennis, G., & Haigh, R. (2024). Enabling horizontalisation. In Implementing Psychologically Informed Environments and Trauma Informed Care: Leadership Perspectives.

Brinckman, B., Alfaro E., Wooten W., Herringa R. (2024). The promie of compassion-based therapy as a novel intervention for adolescent PTSD. Journal of Affective Disorders Reports, Vol 15, (Jan), 100694.

Catalan A, Diaz A, Angosto V, Zamalloa I, Martinez N, Guede D, Aguirregomoscorta F, Bustamante S, Larranaga L, Osa L, Maruottolo C, Fernandez-Rivas A, Bilbao A, GonzalezTorres M.A. Can childhood trauma influence facial emotional recognition independently from a diagnosis of severe mental disorder? Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment(Engl Ed) julsep;13(3):140-149

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Ten Leading Causes of Death and Injury. Injury Prevention and Control. [Online] 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/LeadingCauses.html

Cockersell, P., & Marshall, S. (2024). Implementing psychologically informed environments and trauma informed care. Informa. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003415053

Cristea, I. A., Legge, E., Prosperi, M., Guazzelli, M., David, D., & Gentili, C. (2014). Moderating effects of empathic concern and personal distress on the emotional reactions of disaster volunteers. Disasters, 38(4), 740–752.

Cruz-Gonzalez M, Algeria M, Palmieri P, Spain D, Barlow R, Shieh L, Williams M, Srirangam, Carlson E. (2022). Racial/ ethnic differences in acute and longer-term posttraumatic symptoms following traumatic injury or illness. Psychol Med. Aug;53(11):5099-5108.

Cvetovac, M. E., & Adame, A. L. (2017). The wounded therapist: Understanding the relationship between personal suffering and clinical practice. The Humanistic Psychologist, 45(4), 348.

De Bellis, M. D., & Zisk, A. (2014). The biological effects of childhood trauma. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23, 185–222.

Devi F, Shahwan S, The WL, Sambasivam R, Zhang Y.J., Lau Y.N., Ong S.H., Fung D, Gupta B, Chong S.A, Subramaniam M. (2019) The prevalence of childhood trauma in psychiatric outpateints. Ann Gen Psychiatry. Aug 14;18:15.

Dunbar, R. (1998). The social brain hypothesis. Evolutionary Anthropology, 6(5), 178–190.

Easton, S.D. (2013). Disclosure of child sexual abuse among adult male survivors. Clinical Social Work Journal 41(4), 344-355.

Elvin G, Kurt Z, Kennedy A, Sice P, Walton L, Patel P.(2023) A self-monitoring wellbeing screening methodology for keyworkers, ‘My personal wellbeing’, using an integrative wellbeing model. BMC Health Serv Res. Mar 14;23(1):250.

Fannen, L. (2021). Warp and weft: Psycho-emotional health, politics and experiences. Active Distribution.

Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., & Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study.

American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14, 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S07493797(98)00017-8

Floen S.K, Elklit A (2007). Psychiatric diagnoses, trauma, and suicidality. Annals of General Psychiatry 6(12).

Ford J.D., Grasso D..J, Elhai J.D., Courtois C.A. (2015). Social, cultural, and other diversity in the traumatic stress field. Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. 503-46

Franklin, T. B., Russig, H., Weiss, I. C., Graff, J., Linder, N., Michalon, A., Vizi, S., & Mansuy, I. M. (2010). Epigenetic transmission of the impact of early stress across generations. Biological Psychiatry, 68(5), 408–415.

Gamma, C.M.F., Portugal, L.C.L., Goncalves, R.M. et al (2021). The invisible scars of emotional abuse: a common and highly harmful form of childhood maltreatment. BMC Psychiatry 21, 156 .

Haigh, R. (2013). The quintessence of a therapeutic environment. Therapeutic Communities: The International Journal of Therapeutic Communities, 34(1), 6–15.

Herman, J.L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. Vol 5, Issue 3, 377-391.

Herman, J. L. (1992). Trauma and recovery: The aftermath of violence-from domestic abuse to political terror. Basic Books.

Home Office. Domestic Abuse Act 2021: overarching factsheet. GOV.UK, Home Office Policy Paper.

Hübl, T. (2023). Attuned: Practicing Interdependence to Heal Our Trauma—and Our World. Sounds True.

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K. A., Sethi, D., Butchart, A., Mikton, C., ... & Dunne, M. P. (2017). The effect of multiple adverse childhood experiences on health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Public Health, 2(8), e356–e366.

Hülsheger, U. R., Alberts, H. J., Feinholdt, A., & Lang, J. W. (2013). Benefits of mindfulness at work: The role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98(2), 310.

Johnstone, L., & Boyle, M. (2018). The Power Threat Meaning Framework: An alternative nondiagnostic conceptual system. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 1(18).

Johnstone, L., & Kopua, D. (2019). Crossing cultures with the Power Threat Meaning Framework. Psychotherapy and Politics International, 17(2). https://doi.org/10.1002/ppi.1494

Ke S, Hartmann J, Ressler K.J, Liu Y.Y, Koenen K.C. The emerging role of the gut microbiome in posttraumatic stress disorder.(2023). Brain Behav Immun. Nov;114:360-370.

Kennedy A, Thirkle S, Sice P, Patel P (2022). The Co-Production of the Roots Framework: A Reflective Framework for Mapping the Implementation Journey of Trauma-Informed https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.13.22273691

Levine, P. A. (1997). Waking the tiger: Healing trauma: The innate capacity to transform overwhelming experiences. North Atlantic Books.

Maté, G., & Maté, D. (2022). The myth of normal. Random House.

Mathieu, F. (2012). The compassion fatigue workbook: Creative tools for transforming compassion fatigue and vicarious traumatization. Routledge.

Marohn, S., & Somé, M. P. (2014). What a shaman sees in a mental hospital. Walking Times.

Mongelli F, Perrone D, Balducci J, Sacchetti A, Ferrari S, Mattei G, Galeazzi G.M.(2019).