Does Peer Support Work?

Written by Simon Bradstreet

A deceptively simple question with a less-than-simple answer.

This is the first publication in a new demystifying research series from Imroc.

We are starting with a topic that we know from feedback that many people involved with Imroc are interested in, which is research related to peer support.

Our starting point is a deceptively simple question with a less than simple answer.

Does peer support work?

In unpicking this question we introduce and explain various research terms in a way which is understandable and accessible. All technical research terms are underlined and link to our research jargon buster which will grow as we explore more questions and methods.

This paper will also focus on the strengths and limitations of the main research method that is used to answer questions about effectiveness, which are known as Randomised Controlled Trials.

For the most seamless, interactive experience, we recommend reading this publication online. You can also download a print-ready PDF below if needed.

Key Points

Methods related

All research methods have limitations, so it is important to take a critical and informed perspective.

There is a hierarchy of research evidence with certain types of methods more highly prized than others.

Peer support related

Peer support working is at least as effective as non-peer delivered alternatives.

Peer support workers are more likely to support positive outcomes related to recovery and less likely to impact clinical outcomes.

Peer support workers are held to a higher standard of evidence than other professional groups.

There is a need for more high quality Randomised Controlled Trials of peer support working.

The value of peer support extends beyond what can be easily measured in RCTs - we encourage a broad range of fitting research methods.

Summary

This first paper in the demystifying research series explores the question ‘Does peer support work?’ By unpicking this question, we aim introduce and explain various research terms in a way which is accessible.

The paper begins by establishing that peer support, as a system of giving and receiving, is a long-standing human behaviour, predating formal research. However, the focus of much research, particularly in mental health systems, is on the effect of professionalised Peer Support Workers as measured by Randomised Controlled Trials (RCTs).

While RCTs are widely considered a high standard of evidence in mental health research, applying them to complex interventions like peer support presents challenges. These include the lack of a consistent definition of peer support, and variability in control conditions across studies. As a result, systematic reviews, which explore findings across multiple RCTs, have produced mixed results regarding the impact of peer support working.

Reviews suggest peer support is at least as effective as non-peer delivered alternatives and may be particularly beneficial for recovery-oriented outcomes like empowerment. There is less evidence that peer support is effective when focusing on more clinical outcomes, like symptoms or hospital admission. Notably, the quality of the studies included in reviews is often a concern, limiting the confidence in the overall findings.

The article concludes by suggesting ways to improve research on peer support, such as focusing more on peer-delivered interventions and using meaningful control groups. Ultimately, it emphasises that when making decisions about mental health care, this type of research should be one part of a wider evidence picture.

What do we mean by peer support?

It is reasonable to assume that as long as there has been a means of human communication there has been peer support. Have you heard about this new thing called farming? No! Well, you should totally spend time with [insert neolithic name here]. They’ve been doing it for ages and their clan rarely goes hungry these days... You get the picture – peer support is part of our story as a species of big-brained and deeply interconnected animals.

Fast forward millennia and that same principle is being applied in services and systems that are intended to help people experiencing various forms of distress and exclusion, commonly referred to as mental health problems, mental health issues or ‘mental illnesses.’ In this context, peer support has been described as “offering and receiving help, based on shared understanding, respect and mutual empowerment between people in similar situations” (Mead et al., 2001).

Based on learning from self-organising peer support groups and communities, where people shared a common need and unique skills and knowledge derived from personal experiences, the new professional role of peer support worker has emerged. Peer worker roles have grown at pace in many countries over the past few decades, often driven by strong policy commitments as well as demand from people using services.

So, when we ask the question “does peer support work” what we often mean is: “Does peer support working work?”

Neolithic farming - Peer support is not new.

But what about the farmers?

The kind of naturally occurring peer support that has always existed is not generally the subject of research. Much in the same way that things like smiling or parenting are built into human behaviours and societies we don’t usually expect or demand research evidence before doing them. Yes, some things do become part of our culture in the absence of peer reviewed journal published evidence!

The type of self-organising peer support that exists outside formal systems, whether related to activism or self-help has also been subject to limited research. That does not mean that these approaches are unhelpful but when it comes to creating professional peer roles and building them into existing services systems, the demand for evidence increases. Which takes us back to our (admittedly modified) question “Does peer support working work?”

We don’t need research evidence for everything we do.

What does work even mean?

The question of whether a thing we do with people works or not is described in academic circles as effectiveness research. Researchers also tend to use the word intervention instead of thing! There could be many reasons for this, including the need to demonstrate wisdom or to achieve the gentle intimidation of non-researchers. Either way for researchers, particularly those from a health research backgrounds, what work means is… does a specific intervention demonstrate an effect when compared with another intervention, using a particular method of research, known as a Randomised Controlled Trials.

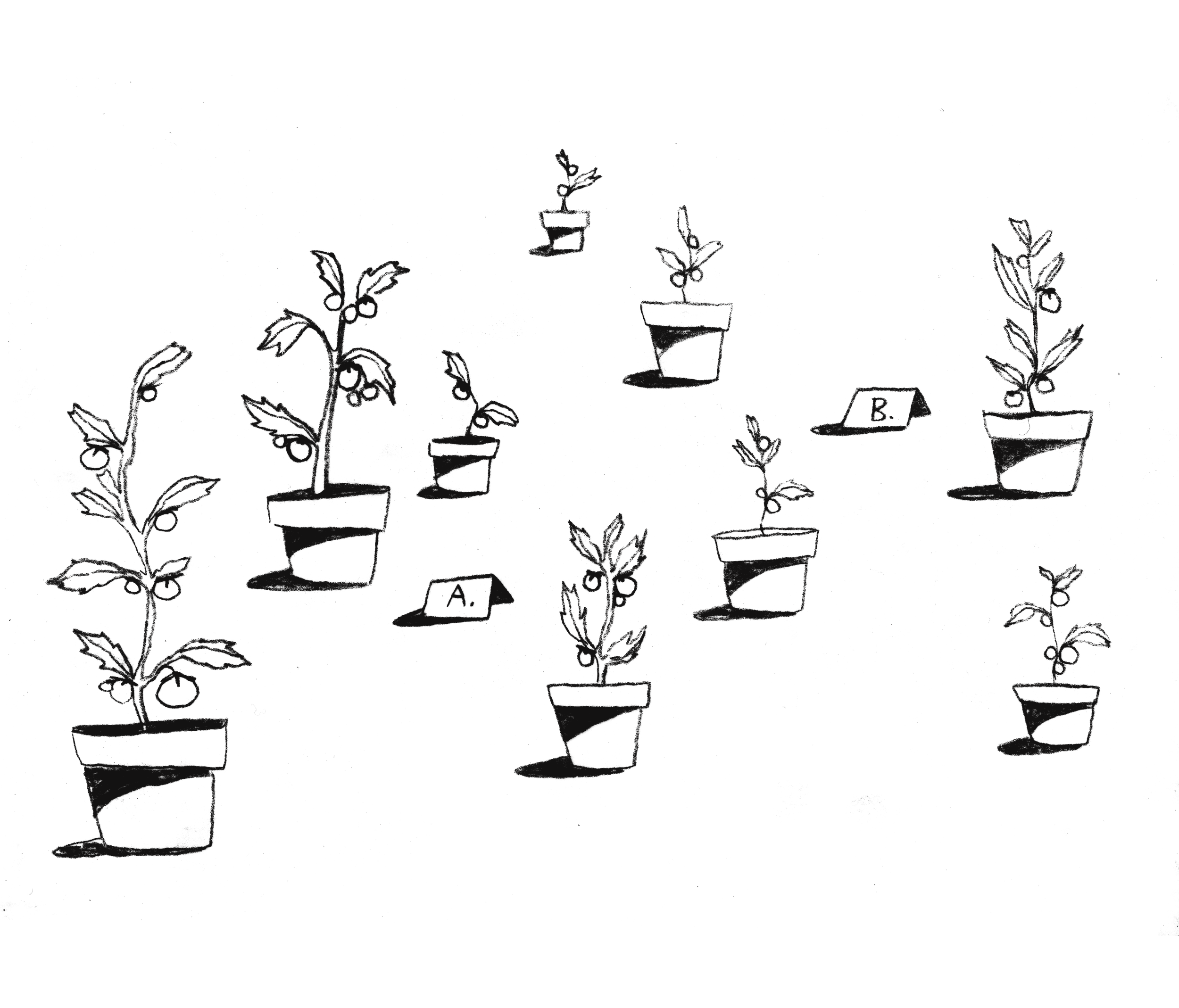

A tomato plant RCT.

OK, so what is a Randomised Controlled Trial?

A Randomised Controlled Trial (RCT) is a type of experimental research design where the people being studied, known as research participants are randomly assigned to different groups, which are usually known as treatment and control groups.

These studies are described as experimental because researchers are seeking to control different aspects of the research including how things are measured and who is recruited to the study. RCT’s collect and analyse quantitative data to test the effectiveness of an intervention or treatment, with the goal of establishing a cause-and-effect relationship. They compare the data that they collect from the control group (which doesn’t receive the intervention being tested), and the treatment group (which does), to see what differences there are and draw conclusions about what effect the intervention has had.

Rightly or wrongly RCT’s are considered to be at the top of a fabled hierarchy of evidence and highly prized by people in health settings. They are a cornerstone of evidence based medicine and, it is fair to say, it is where the serious research funding goes.

There are lots of stories about the origins of RCTs, variously involving long sea voyages and Egyptians, but it’s safe to say they have been around a while and are useful when trying to show that one thing (sorry…intervention) is better than another by randomly assigning people to different groups.

Can you give me an example?

We’ll keep this simple by taking humans out of the equation for just now. Let’s say we want to test the effects of a new type of plant food on tomato plants and whether it makes them grow taller.

To design our RCT we might follow these steps:

Recruit participants: in this case 20 similar sized young tomato plants.

Random Allocation: We randomly divide the 20 plants into two equal groups of 10. We could flip a coin - heads goes to Group A, tails to Group B.

The Intervention: Group A (the intervention or treatment group) gets the plant food as per instructions and Group B (the control group) gets plain old water.

Follow up: Over a set period (say, four weeks), we measure the height of all the tomato plants every week. We make sure all the plants get the same amount of sunlight and water (except for the plant food).

Analysis stage: At the end of the four weeks, we compare the average height of the plants in Group A to the average height of the plants in Group B. If the plants in Group A are significantly taller than those in Group B, we might have evidence that the new plant food has an effect.

The key here is the random allocation in step two. This helps ensure that the two groups are as similar as possible at the start, so we can have a high degree of confidence that any differences we see in plant height at the end are due to the plant food and not some other pre-existing difference between the groups.

In trials random allocation is a key step.

A high degree of confidence sounds a bit vague…

RCTs are based on statistical methods that involve testing the effect of one intervention against another with a large enough group of people. If the difference in effect for an agreed outcome across all of the people in the study is considered to be statistically significant then the intervention is considered to have an effect, or in our words, it works!

Statistical significance is a tool to help people be more confident that the outcomes that they are seeing is a real effect and not just random chance. If a test shows a very low probability of something being a coincidence (for example, less than a 5% chance), the finding is described as statistically significant.

But how do you know it is the thing that worked and not something else?

RCTs are designed to control for the effects other factors (also known as variables). It is a lot easier to control for these kind of external factors, also known as confounding variables, in tomato plants than it is when studying humans. When it comes to things, sorry, interventions that are highly reliant upon interactions between people, like peer support working, then it is becomes even harder to control for all of the things that may be externally influencing results.

That is one of the reasons why the results of many research studies are hard to reproduce when they are repeated. This is also seen in research related to psychology and has been described as a replication crisis. If we don’t get the same results by doing the exact same research study, how can we say that the intervention is reliable?

To address this, people running trials use methods like developing manuals and providing training to try and make sure that interventions are being consistently delivered. Trial researchers refer to this as fidelity. In our case that could mean a manual describing a particular approach to peer support and some assessment of peer worker fidelity to that manual to make sure that people are getting consistent peer support. Whether or not you can manualise something like peer support, which is so contingent upon the quality of relationship and the trust build through that relationship is another question.

RCTs have many potential limitations which have been widely discussed in the literature. These include questions about how representative people recruited to studies are of the wider populations (Kennedy-Martin et al., 2015) and questions over their superiority to other methods when assessing how helpful treatments are (Concato et al., 2000). Like them or loathe them the fact is RCTs rule the evidence roost, and while we can certainly advocate for more fitting methods and better study design, they aren’t going away any time soon. All the more reason to take a critical perspective when reviewing findings.

Please – just get back to the question!!

Over the past few decades, as peer worker roles have increased globally, there has been an explosion of related research. Some of it was seeking to answer our question by using Randomised Controlled Trials.

In these trials, various forms of peer support are considered to be an intervention, and its effectiveness is then compared to a control condition. This means there has been a lot of variation across studies. For example, while most have focused on one-to-one peer support, some have focused on group-based approaches. The setting for the peer support has also varied widely, as has the status and training of the peer supporters involved, and the tools or approaches they were using. This makes it harder to compare across studies because the interventions are different.

Control conditions (the things which an intervention is compared to) also vary across studies. For example, in some trials peer support is compared to the same thing being delivered by non-peer staff. This was very common in early US based trials of peer support where it was being compared with case management delivered by non-peer workers. Other trials have compared different forms of peer support while others compare peer support to what is known as treatment as usual. This means researchers were testing whether outcomes for a group of people who were randomly assigned to receive peer support were better or worse than those for a group randomly assigned to get, well, what they always got – treatment as usual.

The outcomes which were measured also vary enormously, from more clinical measures like reduced hospital admissions or fewer symptoms, to those which are more aligned with recovery, like increased hope, empowerment or increased social connection.

Comparing apples with pears.

So, all that makes it impossible to compare findings across different peer support studies - right?

If Randomised Controlled Trials are at the top of the fabled hierarchy of evidence than systematic reviews are touching the research clouds.

Systematic reviews are research studies that are based on reviewing existing research, in our case Randomised Controlled Trials about peer support working. The systematic word means that these reviews use specific methods, that could be repeated by other researchers, to identify, select, and then critically appraise relevant studies. Review findings are synthesised to provide as unbiased and reliable an assessment of the current state of knowledge for a given topic as possible. As a result, these reviews are highly prized by people who make decisions about how to make policy and use resources.

Jumping from the hierarchy of evidence with an umbrella review.

What do systematic reviews tell us then?

Well, there have been at least 23 systematic reviews that have looked at the effects of peer support working. We know this because, believe it or not, there has been a systematic review of these systematic reviews (Cooper et al., 2024). In fact, there have been two (Yim et al., 2023)!

This type of mega review is known as an umbrella review. It is fair to say that you might need an umbrella (or even better a parachute) to help break your fall when you are this high up the hierarchy of evidence! We’ll get back to the lofty heights of the umbrella review in a bit, but first what can we take from the systematic reviews?

It’s beyond the scope of this paper to summarise the findings on effectiveness from 23 reviews (we’ll leave that to the umbrella reviewers) but crudely, some of the things we can conclude are that peer support working is at least as effective as non-peer delivered alternatives, so that’s good. Put another way outcomes for peer support are no more effective when directly compared with other mental health workers doing similar work.

We also see that peer support workers are better at achieving certain outcomes than others. Generally, these are considered to be outcomes that have a stronger connection to recovery, for example, empowerment, and not outcomes which might be described as being more clinical, for example, reduced symptoms or fewer hospital admissions.

Reviews undertaken by the organisation Cochrane are widely regarded as being of the highest quality and therefore the most reliable. There has been one Cochrane review of peer support working (Pitt et al., 2013). It was the only review included in the previously mentioned umbrella review to be rated as high quality. It included 11 Randomised Controlled Trials involving 2796 people. It found a small reduction in use of crisis or emergency services for people using peer services. It also found peer workers were no better or worse than professionals employed in similar roles when it came to other outcomes like reducing symptoms and service use.

Other reviews have reached slightly different conclusions. One review, which included some group-based peer support, found it had a moderate effect on hope compared to the control group (Lloyd-Evans et al., 2014), while a later review did not replicate this finding but did find evidence for a modest but significant improvement in empowerment and self-reported recovery (White et al., 2020).

Exceptions to the general rule that peer support does not impact clinical outcomes come from two reviews of peer support for perinatal mental health. These showed peer support had an effect improving perinatal depression (Fang et al., 2022; Huang et al., 2020).

We’ll leave the last word to the most recent umbrella review: “results were mixed” (Cooper et al., 2024). This is something researchers say a lot, often just before they tell us that “more research is needed.”

I thought reviews were ‘replicable’ - why do they all say different things?

Different systematic reviews use different standards and processes, which may determine which studies to include or exclude. They also adopt different approaches to analysing information from the studies they include and of reporting their findings. As a result, findings inevitably vary between systematic reviews based on the choices made in each. That’s one of the reasons why umbrella reviews can be useful in providing a high-level overview of the current state of knowledge.

Is there anything they do agree on?

Yes. One thing the reviews agree on is that the quality of the studies included in the review is generally not great and that this reduces the confidence we can have in their findings.

There are agreed tools and methods used to assess quality in systematic reviews. These have strong emphasis on risk of bias, as a result of the methods used in the included studies. For example, if research participants (or researchers) are aware which arm of a trial they have been randomly assigned to. This is known as blinding or, more accurately here, a lack of blinding and is proven to bias results. It is an obvious challenge in trials comparing peer support with treatment as usual. One way to address this is to compare the intervention with what is known as an active control. That might mean comparing one form of peer support with a non-peer provided alternative or comparing different forms peer support.

What about other professional groups – do they work?

This is a very good question. Peer Support Working is the new kid on the mental health workforce block. This creates a clamour for evidence that they work. If we are going to go the bother of recruiting and training peer workers, then we need to know it’s going to be worth the effort, kind of thing.

However, when other professional groups are involved in trial research the focus tends to be on the intervention and not on the person delivering it. For example, there have been thousands of trials of psychological interventions like Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) most of which are, not surprisingly, delivered by psychologists. However, the question in these trials tends to be Does CBT work? and not Do psychologists work?

Top tips for improving evidence for the effect of peer support?

Researchers have provided a range of suggestions for improvement. These include trials being more focused on testing the effect of peer delivered interventions and less on the effect of peer support workers. Some people are very uncomfortable with the idea of turning peer support into an intervention at all. Peer support is fundamentally about good quality relationships, founded on shared learning and reduced power imbalances, they would argue, and any attempts to manualise the approach runs the risk of diluting the very thing you are seeking to find evidence for.

However, it’s probably safe to assume that trials will continue to be the main approach used to justify change and innovation. While we encourage a broader range of methods and evidence, trials could be improved by measuring outcomes that are most closely aligned to the values of peer support. That means focusing less on clinical outcomes and more those related to wellness, social connection and recovery, where most effects have been evidenced.

Trials could also be improved by including meaningful control groups wherever possible. For example, studies comparing different forms of peer-delivered interventions could help us better understand how change happens.

There have also been calls for wider research on what is really happening in good peer support (King & Simmons, 2018; Watson, 2017; White et al., 2020). People often talk about the magic of peer support with real passion but also in quite general terms. Researchers describe unpicking that magic as exploring the mechanisms of change. While theories have been drawn upon to inform research about peer support (Davidson et al., 2012; Solomon, 2004) and reviews have proposed core mechanisms for peer support (Watson, 2017), better understanding these processes would allow for better and more fitting research.

Systematic reviews are touching the evidence clouds.

Whatever the evidence says, isn’t there a moral case for peer support working that should be considered when making decisions?

Yes. The value of peer support extends beyond what can be easily measured in RCTs. To better understand peer support we encourage the use and valuing of a range of fitting methods and less, no matter where they sit on a manufactured hierarchy of evidence.

It’s also important to keep in mind that in ‘evidence based’ approaches, as they were originally conceived, RCTs should only ever be what Druss and Jones (2025) recently described as one leg of a three legged stool: “in which clinical care rests on an optimal balance between clinical expertise, research evidence, and the values, preferences, and characteristics of service users.”

While highly prized, we have to conclude that RCTs are not a good way to understand or assess the effectiveness of peer support. The existing evidence base for peer support is severely limited by problems associated with the methodology and any number of reviews is not going to fix those underlying issues. In fact, if anything, they add to the confusion. However, while trials remain atop the hierarchy of evidence we can at least raise awareness of their strengths and limitations while we advocate for alternative ways of knowing.

-

Concato, J., Shah, N., & Horwitz, R. I.(2000). Randomized, Controlled Trials, Observational Studies, and the Hierarchy of Research Designs. New England Journal of Medicine, 342(25). https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200006223422507,

Cooper, R. E., Saunders, K. R. K., Greenburgh, A., Shah, P., Appleton, R., Machin, K., Jeynes, T., Barnett, P., Allan, S. M., Griffiths, J., Stuart, R., Mitchell, L., Chipp, B., Jeffreys, S., Lloyd-Evans, B., Simpson, A., & Johnson, S. (2024). The effectiveness, implementation, and experiences of peer support approaches for mental health: a systematic umbrella review. BMC Medicine, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03260-y

Davidson, L., Bellamy, C., Kimberly, G., & Miller, R. (2012). Peer support among persons with severe mental illnesses: a review of evidence and experience. World Psychiatry, 2(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.009

Druss, B. G., & Jones, N. (2025). Evidence-Based Practicing in Mental Health. JAMA Psychiatry, 82(5). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.0010

Fang, Q., Lin, L., Chen, Q., Yuan, Y., Wang, S., Zhang, Y., Liu, T., Cheng, H., & Tian, L. (2022). Effect of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: A meta-analysis. General Hospital Psychiatry, 74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2021.12.001

Huang, R., Yan, C., Tian, Y., Lei, B., Yang, D., Liu, D., & Lei, J. (2020). Effectiveness of peer support intervention on perinatal depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. In Journal of Affective Disorders, 276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.048

Kennedy-Martin, T., Curtis, S., Faries, D., Robinson, S., & Johnston, J. (2015). A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-1023-4

King, A. J., & Simmons, M. B. (2018). A systematic review of the attributes and outcomes of peer work and guidelines for reporting studies of peer interventions. In Psychiatric Services. 69(9). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700564

Lloyd-Evans, B., Mayo-Wilson, E., Harrison, B., Istead, H., Brown, E., Pilling, S., Johnson, S., & Kendall, T. (2014). A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials of peer support for people with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-14-39

Mead, S., Hilton, D., & Curtis, L. (2001). Peer support: A theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2). https://doi.org/10.1037/H0095032,

Pitt, V., Lowe, D., Hill, S., Prictor, M., Hetrick, S. E., Ryan, R., & Berends, L. (2013). Consumer-providers of care for adult clients of statutory mental health services. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004807. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004807.pub2

Solomon, P. (2004). Peer Support/Peer Provided Services Underlying Processes, Benefits, and Critical Ingredients. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 27(4). https://doi.org/10.2975/27.2004.392.401

Watson, E. (2017). The mechanisms underpinning peer support: a literature review. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6). https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1417559

White, S., Foster, R., Marks, J., Morshead, R., Goldsmith, L., Barlow, S., Sin, J., & Gillard, S. (2020). The effectiveness of one-to-one peer support in mental health services: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02923-3

Yim, C. S. T., Chieng, J. H. L., Tang, X. R., Tan, J. X., Kwok, V. K. F., & Tan, S. M. (2023). Umbrella review on peer support in mental disorders. International Journal of Mental Health, 52(4). https://doi.org/10.1080/00207411.2023.2166444