Imroc Autism Peer Support Training

Dr. Katja Milner, Imroc Associate Consultant

With thanks to Matter of Focus

Executive Summary

Background

Imroc is committed to building a neuro-inclusive society and developing neuro-affirming practices that prioritise understanding and validation of neurodivergent identities. Research and policy findings highlight the urgent need to support neurodivergent individuals, who face significant gaps in health services and support, as well as widespread bullying, isolation, and marginalisation.

Imroc has led the development, design and delivery of training for peer support workers in England for over fifteen years. This evaluation examines the Imroc autism peer support worker training, the first national programme in England specifically designed for autistic individuals (and their families/carers) to prepare them for peer support roles. Developed through co-production with autistic people, the programme aims to create a safe, neuro-inclusive, and trauma-informed environment, and to empower learners to support others while valuing lived experience as expertise. The aim of the evaluation was to explore how the autism peer support worker training contributes to learning and development in trainees which allows them to go on to thrive within their roles.

Evaluation Approach

This evaluation has been carried out with support from independent organisation, Matter of Focus, using a Theory of Change model. Data was used that is routinely collected during Imroc’s peer support training, as well as collecting data specifically for the purpose of this evaluation. The evaluation focussed primarily on the feedback and lived experiences of those involved including trainers, trainees and organisational leads.

Key Findings

“Once they [learners] are in an environment that moves away from the deficit-based concept of autism they begin to reevaluate themselves. Trainees have reported on several occasions that it has been life changing. They have felt empowered not only to create a better life for themselves but also to create a better world for other autistic people.”

(Imroc Autism Peer Support Worker Trainer)

The evaluation highlights the transformative effect of the programme for both trainees and trainers. Participants consistently describe the training as a rare and empowering opportunity to explore their identities, drawing strength from an environment that celebrates difference rather than focusing on deficits. The course’s co-production model, personalised and trauma-informed approach, and strong emphasis on lived experience and reciprocity underpin its effectiveness.

Trainees report increased self-awareness, self-acceptance, and confidence, describing the experience as life-changing. The learning environment, carefully cultivated by a dedicated team of mainly autistic trainers, is characterised by trust, flexibility, and genuine inclusion. Trainees feel their needs are understood and supported, with accessible materials, personalised adjustments, and a focus on practical peer support skills. The sharing of lived experience is central, fostering reciprocity and a supportive community in which both trainers and trainees continue to learn from one another.

The programme’s impact extends beyond individual development. Many trainees feel newly motivated to advocate for themselves and others, both within and outside their organisations. Some have already initiated changes in workplace policies or practices, contributing to broader organisational and cultural shifts. However, the evaluation also identifies ongoing challenges, particularly regarding the need for robust organisational engagement and support to ensure that newly qualified peer support workers can thrive in their roles.

Trainers themselves have demonstrated considerable skill, resilience, and openness as they navigate the complexity of supporting diverse learners. The emotional and practical demands of this work are significant, highlighting the importance of ongoing trainer support and team cohesion.

Conclusion

The Autism Peer Support Worker Training programme has proven to be a highly effective and valued initiative, providing a unique, empowering, and transformative learning environment. Participants emerge with new skills, a stronger sense of self, and the confidence to advocate for change—outcomes that are both professionally and personally meaningful. The training team’s commitment to Imroc values and reciprocal learning based on lived experience creates safe spaces for participants to develop authentic professional identities. The programme’s emphasis on trust-building enables profound personal development, with many participants experiencing validation and belonging for the first time. The programme stands as an example of what can be achieved when co-production, lived experience, and inclusive values are placed at the centre of training design and delivery.

Recommendations

To further strengthen the programme and support its sustainability, the evaluation recommends:

Enhanced organisational engagement to ensure that trainees are well supported in their roles and that employers fully understand the unique value of autism peer support workers.

Further developing trainee preparation to ensure all participants feel informed and ready to engage with the training.

Robust trainer support systems for trainers, recognising the complexity and emotional demands of their work.

Post-training support and organisational preparation to better prepare trainees and organisations for peer support worker roles and challenges.

Enhanced evaluation data collection including personal development and post-training outcomes and long-term impact.

Introduction

Peer Support is described as “a system of giving and receiving help founded on the key principles of respect, shared responsibility, and a mutual agreement of what is helpful” (Mead et al., 2001). In the context of mental health recovery, the role of peer support work is developing as a central approach that focusses on sharing lived experiences and understanding to facilitate finding meaning, hope and ways to live well (Repper et al., 2021).

Strong empirical evidence demonstrates that employing peer support workers leads to positive benefits (Charles et al., 2021; Slade et al., 2018). Peer support workers contribute to improvements in experiences and outcomes including increased empowerment, engagement and satisfaction, alongside improvements in community integration, social functioning and employment stability. They also drive cultural change within organisations, bringing lived expertise that contributes to more humane, sensitive and person-centred practices (Repper et al., 2021).

Imroc is internationally respected as a centre of excellence in recovery-focused mental health innovation, consultancy and training. For over fifteen years, Imroc has led the development, design and delivery of training for peer support workers across voluntary, statutory, primary and secondary care services in England. Early peer training courses focused on people with mental health conditions, and these have been continually reviewed and developed based on feedback from trainers, trainees, employing organisations and people receiving peer support. Learning from this feedback has been published in a series of Imroc briefing papers (Repper et al., 2013; Repper et al., 2021).

A 2022 independent evaluation by Matter of Focus found very strong evidence that Imroc’s mental health peer support worker training course is effective, with the training team being highly skilled in their approach and embodying Imroc’s peer support values (Bradstreet & Buelo, 2023). These values include building mutual and reciprocal relationships, being recovery-focussed, trauma-informed, person-centred and strengths-focussed. The evaluation identified areas for development including further considerations around diverse trainee needs and increased accessibility options. Specifically, the training was not found to be accessible for some neurodiverse and autistic trainees. In 2022, a co-production group was established to develop a peer support training programme specifically for supporting neurodivergent and autistic learners.

Neuro-Inclusive Approach

Imroc champions building a neuro-inclusive society through neuro-affirming practices that validate neurodivergent identities. Imroc describes neurodiversity as the recognition that all people’s brains work differently, respecting such differences as natural variations which might include neurotypes such as autism, ADHD, dyslexia and more. ‘Neurodivergent’ refers to individuals whose brain function diverges from what is considered ‘typical’ while acknowledging everyone experiences the world uniquely. Imroc recognises that neurodivergence is not something to be ‘fixed’ or recover from because it represents natural and valuable human diversity. Rather, society must adapt to neurodivergent ways of experiencing and interacting with the world.

In 2019, the NHS Long Term Plan identified key areas requiring urgent action to support neurodivergent people, particularly autistic people and their families. Gaps in diagnosis, health and social support and implementation were highlighted, as well as inadequate service provision. Historically neurodivergent voices, especially those of autistic people, have been marginalised and misrepresented leading to misunderstanding of their needs. The Long Term Plan identifies key challenges including inadequate healthcare adjustments, low employment rates, insufficient community-based support, bullying and isolation.

Programme Development

Imroc’s autism peer support training focusses on empowering neurodivergent people through neuro-affirming practices to support self-advocacy and the skills to effectively support others through peer support and sharing lived experience. It aims to promote a greater understanding of neurodivergent experiences within society and help transform systems and services to create equitable opportunities for neurodivergent people. Imroc’s peer support training programmes are developed and delivered by individuals with lived experience, creating safe, supportive and trauma-informed environments where diverse individual needs are continually responded to.

Because peer support is founded on the cultivation of mutual and reciprocal relationships between people with lived experience, coproduction is central to every aspect of training development, delivery and evaluation. Imroc established an autism coproduction group (ACG) to review existing peer support training and coproduce training materials supporting achievement of competencies on the Capability Framework for Autism Peer Support Workers published by Health Education England (HEE, 2022). A training programme was piloted and underwent several iterations before being agreed for delivery. The resulting programme was the first national training for autistic peer support workers and their family/carers and was commissioned by HEE.

Programme Structure

The course combines theory and evidence of peer support with a practical focus on tools for application within autism peer support worker roles. An estimated 80% attendance equips people well to begin working with others in such roles. The course duration is approximately 60 hours total, comprising 15 core modules delivered online as 2.5-hour sessions with one or two modules completed weekly.

The 15 modules cover the foundations of peer support, including creating safe learning spaces, building relationships based on values, working in person-centred ways, and supporting people through change. The course also explores key themes such as rights and entitlements, inclusion, safety, wellbeing at work, and the use of lived experience in supportive and ethical ways.

Two additional optional modules are available — one focusing on ADHD, neurodevelopmental conditions and learning disability, and the other on co-occurring physical and mental health needs. These optional modules are also open to the wider workforce.

Methodological Approach

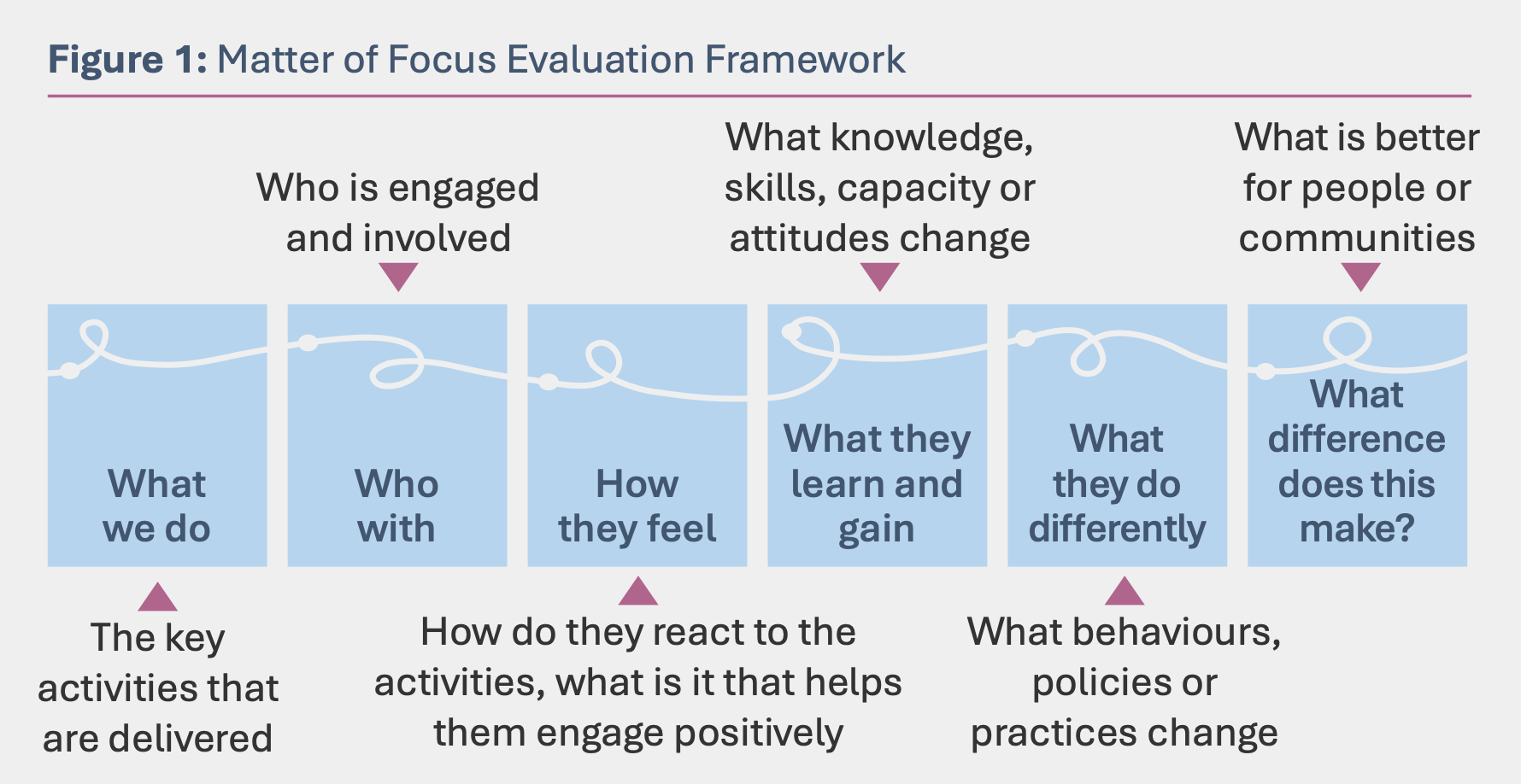

This evaluation uses a theory-based approach developed by Matter of Focus to support organisations working with complex people-based change. The approach is underpinned by a ‘Theory of Change’ framework that uncovers if and how initiatives contribute to change by breaking this process into meaningful steps, as shown in Figure 1 overleaf.

Figure 1: Matter of Focus Evaluation Framwork

These stepped areas of enquiry create an ‘outcome map’ providing an evaluation framework for tracking progress and inputting findings. The approach is supported by ‘OutNav’ software, providing a single platform for evaluation planning, analysis and reporting.

Multiple data sources were collected and analysed to develop and evaluate a theory of change demonstrating if and how the autism peer support training programme achieves key outcomes. These sources included both routinely collected Imroc data and information gathered specifically for this evaluation. A co-production approach was employed, which involves creating opportunities for meaningful participation of those with lived experience at each stage of the evaluation process. Working alongside trainees and trainers, the evaluation focused on their experiences and perspectives rather than assessing training materials or organisational contexts. The theory of change that was developed and illustrated using the outcome map was then tested by collecting data and examining whether the assumptions and outcomes in the theory of change are supported in practice.

Data Collection

1. Analytical workshops

The first stage of data collection involved setting up four analysis workshops which spanned the course of the evaluation between March and September 2024. Autism peer support trainers and training leads were invited, and the workshops were facilitated by Matter of Focus and Imroc consultants.

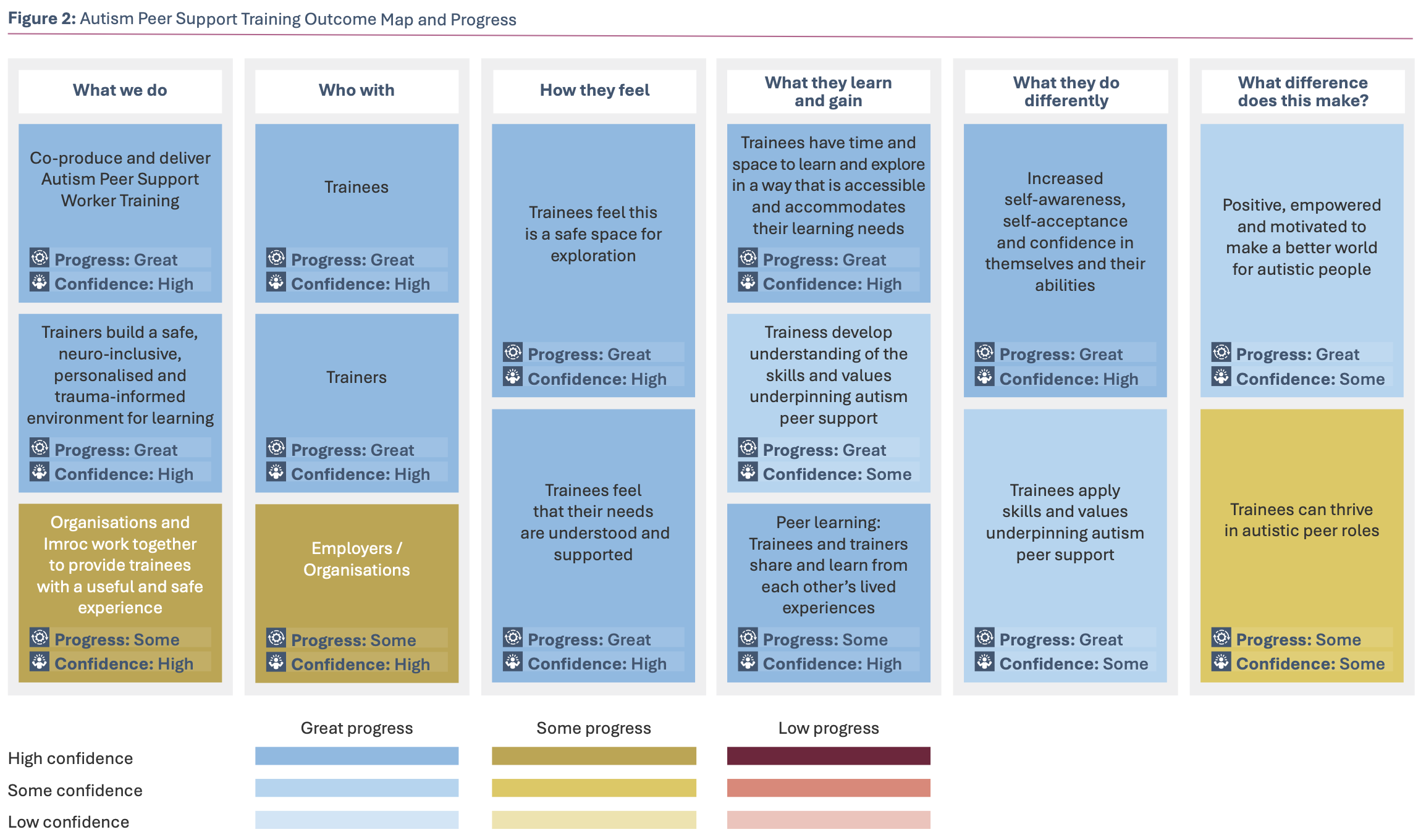

The workshops aimed to co-produce and refine the outcome map which would be used to underpin the evaluation framework (Figure 2). Accessible ‘Miro board’ technology, virtual post-it notes, group chat, and online discussions were used for participants to contribute their reflections. These sources, facilitator notes and initial analyses were used to create the initial outcome map, with subsequent workshops discussing and agreeing further outcome map iterations.

During the final workshop, each ‘stepping stone’ of the outcome map was assessed regarding available evidence and progress made. Outcome map colours reflect this assessment: blue showing good progress, yellow showing some progress, and red showing no evidence of progress (Figure 2). Colour strength shows confidence degree in evidence, with strong colours indicating high confidence and pale colours indicating low confidence.

2. Context Mapping

A context mapping exercise was completed during the first analytical workshops to identify individual, social and material factors influencing programme outcomes. Considerations of contextual factors can contribute towards more rigorous analysis and are used to derive a set of risks and assumptions. Risks and assumptions highlight important influences upon the change process including barriers and aids towards success. The key risks and assumptions highlighted by the training team are shown in Figure 3.

3. Additional Data Sources

Additional data sources included:

Routinely collected demographic data

Trainee evaluation forms (2022–2023) including quantitative and qualitative components

Programme lead and trainer discussions

Training materials and pilot study report examination

Additional trainer feedback and reflection logs (limited response)

Data analysis

Data was systematically organised according to outcome map stepping stones, with themes emerging in participants’ own language. Findings were reviewed by both Matter of Focus and Imroc teams to ensure rigorous analysis before developing the overall evaluation narrative.

Autism Peer Support Training Outcome Map and Progress

Figure 2: Autism Peer Support Training Outcome Map and Progress

Risks and Assumptions

Figure 3: Risks and Assumptions – potential factors which may influence autism peer support worker training outcomes

Detailed Findings

Analysis of evidence from the autism peer support training shows positive outcomes and significant progress since the initial training programmes delivered in 2022 and 2023. Findings are structured following the theory of change model, examining core activities, participants, and outcomes achieved. In the following sections, trainer quotes have been used to illustrate findings and themes. Abundant trainee quotes also supported these themes, however, as consent for their use in reporting had not been obtained during completion of evaluation forms, they have not been included in this report.

What we (Imroc) do

Co-produce and deliver Autism Peer Support Worker Training

Progress: Great Confidence: High

Co-production is central to the training design and delivery, acknowledging diverse expertise and valuing contributions through generative conversations. Three foundational Imroc values underpin this process: Hope (believing in potential and building confidence), Control (enabling self-direction), and Opportunity (creating access to meaningful roles and relationships).

The Autism Consultation Group (ACG) developed content through an iterative process, creating modular handbooks available in different formats and colours based on student preferences. Reasonable adjustment templates and one-page profiles address accessibility needs.

Trainers described the processes of co-production and personalised delivery as being complex and multi-layered, often requiring thinking ‘outside the box’ to support trainee participation. They also highlighted the evolving nature of their work, being continually open to improving, refining and adjusting, and with the team becoming increasingly confident through experience. They maintain a reflective, self-critical approach, creating forums for ongoing review and evaluation of modules.

Trainers build a safe, neuro-inclusive, personalised and trauma-informed environment for learning

Progress: Great Confidence: High

Strong evidence demonstrates the training team’s effectiveness in co-creating safe learning environments that are genuinely neuro-inclusive, personalised and trauma-informed.

Pre-programme meetings allow trainees to raise concerns and ask questions. Each student receives allocated tutor support and tutorial group access. Five-point scale check-ins before and after sessions provide an opportunity for students to reflect on their wellbeing and identify support needs.

Trainee evaluation data shows highly positive learning experiences. In 2022, fourteen of seventeen (82%) respondents rated the course ‘Good’ or ‘Excellent’ overall. The 2023 cohort showed improvement, with all six respondents rating the training as ‘Excellent’, indicating successful programme refinements (Figures 4 & 5).

Figure 4: Overall Course Rating for 2022 Peer Support Worker Training Evaluation

Figure 5: Overall Course Rating for 2023 Peer Support Worker Training Evaluation

Analysis of the qualitative data shared by trainers and trainees indicated three key considerations in relation to creating safe, neuro-inclusive personalised and trauma-informed environments for learning. These are: Preparation for Learning; Holding Complexity and Feeling Safe and Supported as a Trainer. Feedback also indicated successful developments between 2022 and 2023, with fewer improvement suggestions in later evaluations. Initial recommendations focused on better preparation of materials and clearer course expectations, leading to enhanced pre-course communication and support.

1. Preparation for Learning

Preparation was a key aspect highlighted by the training team as contributing towards the success of the programme and ensuring a safe, inclusive and personalised learning environment. Considering the past educational and system related experiences of students was a key component of this. Trainees may come to the course with past experiences of being excluded from organisations, education systems and work environments. They may also have negative or traumatic experiences of using services as ‘service-based systemic trauma’. Trainers pointed out that with so many past negative experiences, an autistic person may not feel safe ‘to be themselves’ or to trust a new environment full of strangers.

Despite such past experiences, the training team were confident that with the right level of preparation and skilful facilitation, most trainees could start to feel safe, able to share more openly and enjoy being with like-minded people.

“I wonder if an individual barrier is previous experiences of training and education which may have been very negative and then the wonderful surprise that this is a very different experience. The things people say about the first time they have been in a space with lots of other autistic people is heartwarming.” (Trainer)

A number of qualities were suggested as contributing to creating such a safe space including professionalism whilst modelling peer support, mutual and reciprocal learning, collective wisdom, sharing lived experiences, and establishing a rapport with trainees. The term ‘neuro-affirming’ was mentioned as important to consider alongside being ‘trauma-informed’. The in-depth exploration about what it means to be neuro-diverse was suggested as being key to supporting learning on this training programme, particularly in the context of a world in which this is rarely well established:

“What we do – we build a safe neuro-inclusive space for learning, it is trauma informed but also informed what it means to be neurodiverse in what are usually neurotypical spaces and training.” (Trainer)

Whilst preparing for the training and on-going sessions, trainers talked about the importance of remaining aware of accommodations and reasonable adjustments throughout the training programme:

“We go to great lengths to ensure we have asked people about reasonable adjustments how we can support them to maximise their learning.” (Trainer)

Trainee feedback from their evaluation forms reflected the passion, effort and hard work of the trainers. There was a lot of praise for the trainers, saying that they were knowledgeable, explained the subjects well, engaged in thoughtful discussion and worked well with the input and feedback of the group. Trainers were described as approachable, diligent, patient, engaging, empathetic and welcoming. One trainee commented on how quickly the training team acted on feedback and any concerns raised. Others described feeling supported and comfortable sharing their lived experiences, and that they would highly recommend the course to parents and professionals.

2. Holding Complexity

Trainers discussed navigating unique complexity in accommodating diverse individual needs while continuously assessing reasonable adjustments. Trainers said this led to them sometimes having “so much to hold” and to continually monitor and “read the room” quickly, being ongoingly sensitive, vigilant and flexible to emerging individual trainee needs. As one trainer commented:

“I think it’s because each presentation is so unique the processes are endless and as a team we are flexible to that” (Trainer)

Trainers commented on the impact of holding such complexity upon their own experiences as a trainer:

“The layers of interactions between everyone within the team and within the cohort is different every time and definitely heightens my normal-level anxiety each time we start a new one, despite feeling more comfortable in my role now.” (Trainer)

A key theme which arose from trainers’ experiences of holding complexity was processing time. They highlighted the challenge of processing what they are seeing or hearing and then responding quickly to that within the live online learning environment:

“The processing time element can definitely be a challenge in the moment when we are on the live calls” (Trainer)

Meeting such complex and diverse needs, as well as backgrounds and levels of understanding of the trainees could sometimes lead to anxiety, exhaustion and feelings of overwhelm for the trainers. Despite these challenges, a number of the trainees acknowledged, with gratitude, the skill, resilience, sensitivity and hard work that the training team dedicated to the courses.

3. Feeling Safe and Supported as a Trainer

Trainers emphasised the importance of their own wellbeing as part of effectively holding safe and personalised environments for learning. The team noted the importance of a feeling of safety being there for the training team as much as the trainees, and the direct relationship between trainers and trainees’ experiences.

Building strong values as a team, the development of a trainers manual and team adaptation and mutual support, especially during periods of fluctuating capacity were discussed as essential to feeling supported as a training team:

“Those weeks where people have a child at home or something external going on really make a difference and we are always adapting to support this and support each other within the space.” (Trainer)

Organisations and Imroc work together to provide trainees with a useful and safe experience

Progress: Some Confidence: High

Imroc collaborates with organisations to provide safe, useful experiences for trainees. The process begins with organisations contacting local HEE offices, followed by Imroc engagement to share expectations and assess readiness. Information sessions help organisations understand peer support roles, integration requirements and reasonable adjustments.

Progress has been made in creating strong organisational connections, though challenges remain, including insufficient preparation time, managing training demand, and organisations sometimes enrolling trainees without adequate information or consideration. Trainees sometimes reported feeling nervous and unsure about what they were doing due to lack of information about the training from their nominating organisation. The training team help to reassure enrolled trainees and carry out regular check-ins with tutors in relation to any organisational issues or queries. Ongoing communication with Imroc proved vital for addressing organisational issues and supporting trainee success.

Who With

Trainees

Progress: Great Confidence: High

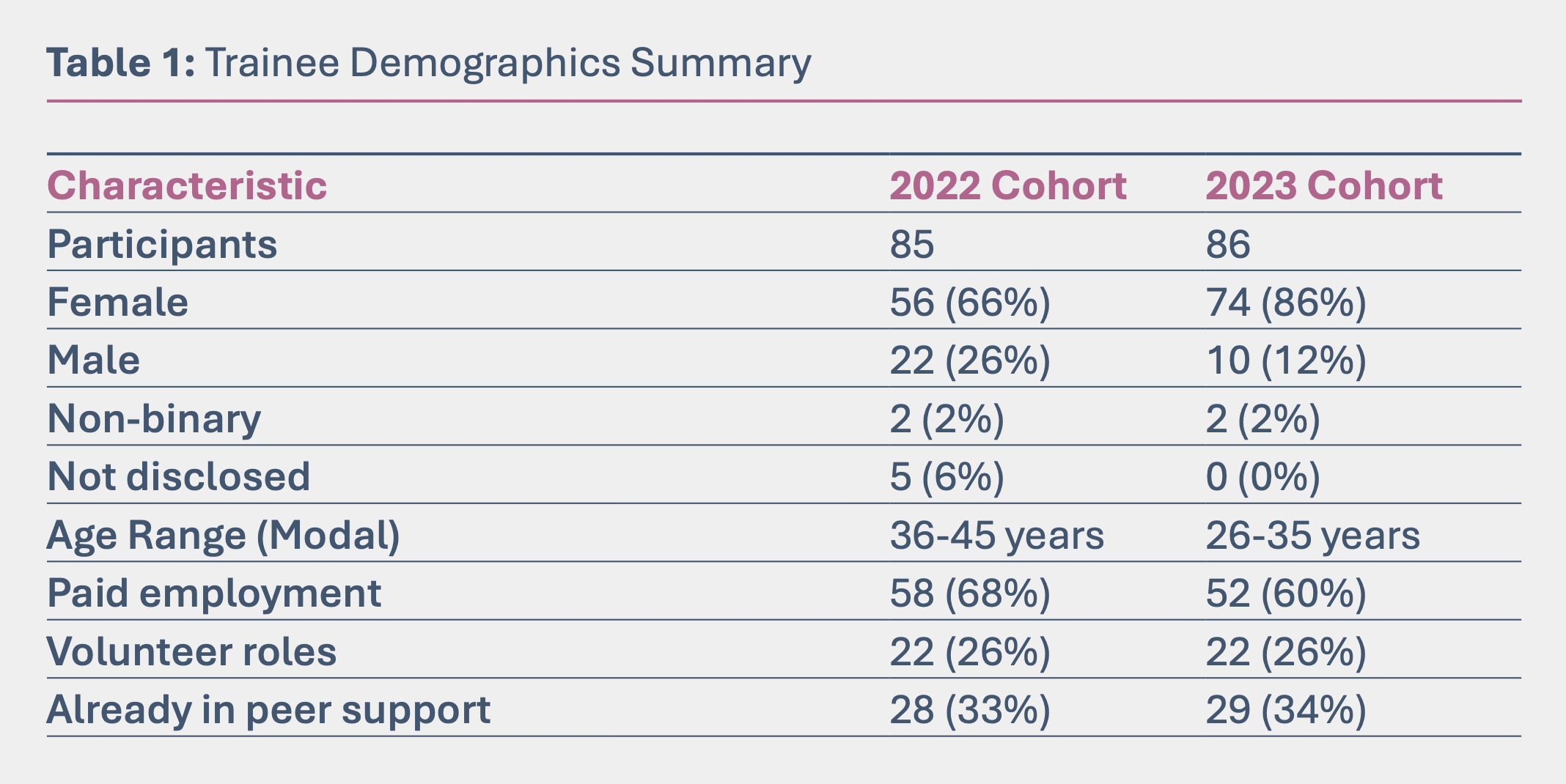

The autism peer support training is aimed at people who identify as autistic, or family, friends or carers of autistic individuals, who will provide peer support in autism services through paid or voluntary roles. Demographic information for 2022 and 2023 training programme cohorts are shown below (Table 1).

There were a similar number of trainees in both cohorts (85 trainees in 2022 and 86 in 2023) with a slightly higher maximum age range in 2022 (36–45 years) than 2023 (26–35 years). Gender distribution showed predominantly female participation (56 females, 10 males, 2 non-binary in 2022; 73 females, 10 males, 2 non-binary in 2023). Ethnic diversity increased slightly in 2023, though overall demographics highlight ongoing needs for greater diversity in peer support workers (Watson & Repper, 2022).

Table 1: Trainee Demographics Summary

Approximately one-third of trainees from both cohorts were already in peer support roles, describing various contexts including diversity support, ADHD peer support, mental health, and disability support. The majority were in paid employment (58 in 2022, 52 in 2023) with 22 volunteers in each cohort.

Trainers work to ensure trainees are optimally positioned for training participation, adopting inclusive recruitment approaches and remaining flexible to unexpected circumstances. The diversity of experiences ranges from students with a Masters level education, to those with learning disabilities requiring additional support, necessitating careful personalisation of learning approaches.

Trainers bring diverse life experiences and professional expertise while committing to Imroc’s values of hope, control, and opportunity. The pilot programme demonstrated how these values felt personally relevant to trainers who had experienced exclusion in past educational and work contexts.

Analytical workshops identified growing trainer confidence as the team increasingly celebrates their unique skills and supports one another’s strengths. One-to-one support structures were identified as being reviewed for enhanced effectiveness.

Trainers

The training team predominately comprises of people who identify as autistic, with some being parents or carers of autistic children. Trainers undergo a structured developmental pathway: beginning as ‘classroom assistants’ with no direct facilitation role in order to practice skills, then progressing to full assessment as competent trainers. Assessment encompasses programme delivery, presentation skills, group facilitation, and one-to-one trainee support.

All team members complete ‘one-page profiles,’ sharing their backgrounds with students and disclosing additional support needs to programme leads. This ensures trainer difficulties are known and are supported by the team. Additional support includes programme lead guidance, regular supervision, weekly development workshops and classroom assistants who monitor online chat and provide general guidance and technical help during training sessions.

Organisations

Progress: Some Confidence: High

Enrolling organisations initially came through NHS connections, though awareness-raising efforts have expanded reach to numerous mental health organisations. Dominant geographic regions for organisations were the Northeast, Yorkshire and Midlands in 2022 and the Northwest, Midlands and Southwest in 2023.

The Programme Lead maintains organisational liaison, with evidence of increasing employer engagement and strong existing relationships. However, scope exists for greater organisational diversity through continued promotional activities including briefing papers, position statements, and general awareness-raising within Imroc.

Gauging the feelings of trainees is important in an evaluation based on the Theory of Change model because evidence suggests that emotional response is an important determinant of engagement in learning. Although direct emotional response data collection requires further development, feedback emphasised the importance of trainees feeling that they could safely explore and that their needs are understood and supported.

Trainees feel this is a safe space for exploration

Progress: Great Confidence: High

Significant progress was achieved in establishing safe exploration environments for learning. This evaluation identified three key themes: Building trust; Reciprocity; and Monitoring feelings, as outlined below.

1. Building Trust

Analytical workshops indicated that there is a trajectory of slowly creating and building trust throughout the course. Trainers commented that it can take time for people to feel able to share and build confidence and for trainers to understand better trainee support needs.

Trainees reported sometimes feeling tentative during the early stages of training due to negative and traumatic past experiences. Such challenging experiences can lead to people with autism having difficulties opening up, feeling safe and that they can be themselves, which is sometimes known as ‘masking’.

Trainers commented that after a slow start, there is often a gradual opening-up and blossoming process. They described that about halfway through the course, trainees often start to show signs of change or what trainers described as ‘unmasking’. This was articulated by some as a process of ‘self-actualisation,’ a term denoting personal or psychosocial development as well as increased confidence, empowerment, and life re-evaluation. Some trainees reflected on the support and feeling of safety received from trainers and the learning environment, which helped them to build confidence after a tentative, nervous start.

2. Reciprocity

Reciprocity within relationships and learning is highlighted as key to creating a safe space and is a strength of the training team. This was described as a “symbiotic process” rather than prescriptive processes. Trainers cultivate trust by embedding programme values, role-modelling peer support, sharing lived experiences, utilising experiential knowledge, and building respectful environments. It was pointed out that the careful recruitment process of trainers contributed to this, and concepts like “the chemistry” and “the vibe” were used to describe the feeling of what could help make the learning environment feel safe and harmonious.

3. Monitoring feelings

A key area for further development is directly collecting information about how safe trainees feel over the course of the programme. Trainers said that trainee progress was reviewed in general and in relation to reasonable adjustments, but this was not always straightforward to discern:

“We monitor participation and this helps us to see if people are comfortable with the space, it’s quite subjective” (Trainer)

“Some trainees report that they have found it a safe space and some trainees are much harder to tell how they feel” (Trainer)

The team discussed extra methods of checking in with trainees around their wellbeing, including session rating scales, breakout room sharing, and gauging check-in/check-out perspectives, with suggestions for software-supported recording and utilisation.

Trainees feel that their needs are understood and supported

Progress: Great Confidence: High

Substantial progress was made in ensuring trainees feel their needs are understood and supported. Trainees described developing coping strategies and confidence and feeling understood and accepted. This was primarily achieved through trainers continually monitoring and adapting to trainees’ needs as the programme progressed. This process was described by one trainer as:

“People having their needs understood… something that reflects all of the work we put in to making accommodations and reasonable adjustments to support everyone… that we are noticing and responding to see how else we can support… what more can we offer… do we need to make different adjustments etc” (Trainer)

Such support begins at the start of the course when trainees complete their ‘reasonable adjustment passport’ and there is good communication with the organisations who enrol trainees. Trainers pointed out that there is a complexity to this process related to the different backgrounds, needs, expectations and aims of each trainee, which they strive to understand and adapt to. However, this relates to the assumption outlined in the context mapping that trainers have adequate time to understand and respond to such needs.

Specific ways the team monitor and adapt to understand and support people’s needs include:

Pre-module team meetings to identify any potential triggers for individuals and how they might be supported to navigate those.

Post-session team debriefing identifying trainees who may require further support and discussion about how to help or adapt the training.

Monitoring online training platform ‘Moodle’ to explore potential support needs.

Non-participation follow-up to explore understanding and support needs.

Offering one-to-one support if required.

Utilising check-in/out data to gain understanding of trainee progress and to identify trainees who may need further support.

In relation to what trainees learn and gain, this evaluation provides strong evidence that the autism peer support training is accessible, cultivates the values of peer support and provides opportunities for trainees and trainers to share their lived experiences.

Trainees have time and space to learn and explore in a way that is accessible and accommodates their learning needs

Progress: Great Confidence: High

It was identified that an essential component to effective autism peer support training is that trainees have the time and space to learn in accessible ways that accommodate their individual learning needs. Evaluation findings highlight that great progress has been made and three key themes were pertinent to this area: Processing time; Online accessibility; and Developments in course content, materials and process.

1. Processing time

Processing time was identified as critical for course accessibility, particularly given online delivery challenges. Processing time is required over the duration of the course for trainees to feel more comfortable and gain confidence. Trainers suggested strategies to support this including the use of break-out rooms, taking time to explain where to find information and providing training materials for trainees to read and process at least one week before the course:

“Trainees having had time to fully engage with all the materials and preparation activities each week really makes a visible difference to their contributions in the live calls” (Trainer)

2. Online Accessibility

Technical issues can be very difficult for trainees and may hinder their interaction with the programme. Although breakout rooms were sometimes offered to support the online experience, some trainees commented that there could be issues with these, such as difficulties reading the room if people had their cameras switched off, or communication differences within that space. Other trainees reported issues with navigating learning over Zoom, downloading information about the course, and a lack of IT support.

Despite these issues, there were also positive comments about the training being online. For one trainee it helped that they did not have to travel to do the course. Others suggested that having conversations about the course outside of the online session was helpful in supporting understanding. Further approaches taken to improve the online learning experience included the use of a chat facility and the patient, empathetic and understanding approach of the trainers.

3. Developments in course content, materials and processes

Evaluation feedback from the 2022 cohort identified multiple accessibility issues including pacing of sessions, long stretches of didactic teaching, timing of group tasks, lengthy blocks of text in the module guide, difficulty accessing relevant sections of the guide and unclear course outcomes and goals.

Numerous suggestions were made by trainees about potential improvements that would support accessibility of learning. These included:

• making the course shorter and the course guide easier to read

• using more concise ways of writing

• summarising each module

• shortening check-in times

• releasing module information earlier.

Trainees had suggestions for improved experiences in the breakout rooms such as clearer instructions and trainers better facilitating these spaces to steer conversations back on course and address oversharing. Others suggested that further space and time for explanations about the course would have been useful.

Feedback from the 2023 cohort showed significant improvements in these areas, though some concerns remained regarding preparation, work expectations and module guide detail levels. One 2023 trainee said they felt nothing needed improving and that the course was outstanding from start to finish.

Trainees develop understanding of the skills and values underpinning autism peer support

Progress: Great Confidence: Some

The first seven modules of the course focus upon core peer support values, while ensuring trainees feel safe, seen, heard, and empowered. During this time trainees start to learn to offer peer support for themselves and others, with their confidence growing particularly after the mid-way point of the course. The skills and values underpinning peer support are continually monitored with feedback given halfway through. The training team reflected that this process could be further formalised which could provide stronger evidence of the course’s impact. Trainers also said that there may be ways for trainees to develop confidence in their skills earlier on in the course.

Trainees identified a variety of skills and values they had learned during the training. These included: active listening skills, patience, perseverance, being able to share life experiences with boundaries, confidence, compassion, honesty, integrity, mutuality, respect and reciprocity. They learned person-centred approaches, appropriate language use, flexibility, self-awareness, empathy and non-judgmental attitudes.

Imroc has developed a comprehensive and detailed approach to assessing student understanding and competence through a ‘Capability Assessment Framework’ which identifies and matches capabilities related to module subjects to student performance. Trainee understanding and competency is assessed through their reflections at the mid-point and end of the training. Students are asked to reflect on their learning as well as considering potential challenges within practice. They are also given regular feedback based on classroom observations.

Difficulties with understanding or application of learning are identified early and the student may access additional support from their tutor, their tutor group or a study group to further develop their understanding. The nominating organisation is updated and informed about student progress and any potential issues with attendance, although attrition rates for students are low.

Peer Learning: Trainees and trainers share and learn from each other’s lived experiences

Progress: Great Confidence: High

Learning from lived experience is a fundamental component of the autism peer support worker training. The evaluation identified that great progress has been made in this area, and there were three key themes: Sharing lived experiences; Learning about autism and neurodiversity; and Family and carer perspectives.

1. Sharing lived experiences

A trainer highlighted that sharing experiences, and doing so appropriately, is at the core of what the programme is all about. The training team discussed how powerful lived experiences are and how they can be used to help others, for example allowing people to be heard and removing barriers to people authentically expressing themselves. There was a consensus that this aspect is what makes this training course particularly unique and powerful, and that it contributes towards reframing people’s experiences of autism. Trainers discussed specific ways they might share their lived experiences to model peer practices:

“There is something around how trainers share their own lived experiences in a way which is safe and boundaried and offers a little vulnerability that in turn allows the trainees to relate and share their own experiences - the word authenticity feels important here.” (Trainer)

A large proportion of trainees commented on evaluation forms that sharing lived experiences was a component that worked particularly well within the training programme. They appreciated the different insights shared within the group, learning from other autistic people to gain more knowledge, and feeling valued whilst sharing their own experiences.

A few trainees acknowledged the challenges that can be involved in openly sharing lived experiences with others, saying they felt nervous at first, or struggled with the way group discussions might unfold.

Many trainees commented that sharing lived experiences contributed towards learning about themselves and how their experiences could be utilised to support and guide others. They said they were able to gain confidence speaking about themselves without feeling judged and appreciated being able to connect with like-minded people.

2. Learning about autism and neurodiversity

The training team highlighted the importance of the programme being an inclusive space in which people can further their understanding of autism and neurodiversity. Cultural differences and other forms of diversity can also be important to consider.

A key theme that can arise when learning about autism is masking, and trainers discussed how this can be most helpfully approached as a topic area for discussion and exploration. They pointed out that there is a complexity to masking, such as having multiple layers, that one may not be aware that they are masking, and the importance of being able to judge where it may or may not be appropriate. As one trainer commented:

“I think masking can become complex for those that are late diagnosed as they may not know they have been masking or have experienced any environments where they can start to explore who they really are and experience new ways of being accepted and find sense of belonging.” (Trainer)

For one trainee, such masking had led to burnout, which they reflected had been an important learning point on the course.

Many trainees fed back positively about their learning of autism on the training programme. They particularly commented on learning about the unique and diverse ways that autism can be expressed in people, noting that the spectrum is broader than expected. Such insights contributed to deeper understandings about differences in struggles and coping mechanisms for autistic people. Trainees said that they particularly enjoyed learning with other autistic people and that doing so could lead to life-changing realisations about themselves. These included realisations that being neurodivergent can be a strength, and fully accepting the diagnosis of autism for the first time.

3. Family/Carer perspectives

Family and carer perspectives comprise a key component of the training programme. An inclusive approach is adopted towards carers and family members of autistic people whether they are autistic themselves or not. At times, such participants questioned the value of attending a programme for autistic people or described challenges in understanding. However, the training team helped to explain the value of the course so that they could better appreciate the importance of learning about the lived experiences of the group.

Feedback from 2022 evaluations about family and carer perspectives were mixed, with some suggesting this topic could have been more thoroughly explored. 2023 evaluations showed unanimous improvement, indicating successful learning integration and commitment to continuous improvement.

Increased self-awareness, self-acceptance and confidence in themselves and their abilities

Progress: Great Confidence: High

The training consistently fostered significant personal and professional development among participants. Two interconnected processes emerged as central to this transformation: personal development through safe learning environments and validation leading to empowerment.

1. Personal development

The programme created a developmental journey where participants initially navigated challenging weeks while adapting to a trust-based learning environment. Over time, trainees experienced what trainers described as ‘unmasking’ and ‘blossoming’, leading to increased self-confidence and authentic self-expression. This process represented both professional skill development and personal self-actualisation, with trainees learning to understand themselves within their lived context.

In this sense, the training programme is not just a teaching and learning experience in relation to working in autism peer support contexts, but an opportunity to have a developmental and potentially life-changing personal experience. By the end of the course the training team said that the atmosphere can feel very celebratory as trainees acknowledge the personal journey they have been on and the confidence they have gained.

Trainees described this developmental process in relation to growing personal and professional awareness, including developing greater understanding about personal bias and professional boundaries, and gaining confidence to share and apply newly acquired skills.

2. Acceptance, validation and empowerment

The training provided validation that proved profoundly empowering for participants. Trainees reported feeling accepted and celebrated for their differences, often for the first time. This validation translated into increased confidence and willingness to advocate for themselves and others, both within and beyond the training context.

The training team emphasised that the course encourages people to accept and celebrate what they do differently and to overcome fears in doing so, especially in light of negative attitudes that can surround the concept of autism. Participants often shared their transformative experiences in moving ways, learning to embrace and celebrate their unique approaches and what they do differently. This shift in perspective proved transformative, with trainees developing stronger belief in their capabilities and potential to create positive change.

Trainees echoed these reflections, highlighting that they had learned to feel more confident about themselves and their skills over the duration of the course, and of the importance of believing in themselves even when they might be struggling with certain tasks. It was highlighted that further information could be captured about trainee experiences of building self-awareness and confidence, including ways these could be empowering and support personal and skill development beyond the training programme.

Trainees apply skills and values underpinning autism peer support

Progress: Great Confidence: Some

Evidence of skill application emerged during group activities, with trainees demonstrating active listening, peer support techniques, and trauma-informed approaches. However, comprehensive evaluation of post-training skill application requires further longitudinal study.

Some trainees, particularly from the 2022 cohort expressed some hesitancy and indicated the need for time to process before applying what had been learned into practice, noting the intensive pace of the programme. Others expressed confidence in applying skills immediately, particularly in communication, active listening, needs identification and applying intricate peer support skills, including boundary management and sustainable working practices.

Trainees are positive, empowered and motivated to make a better world for autistic people

Progress: Great Confidence: Some

Significant evidence has been highlighted throughout this report of trainees and trainers feeling positive and empowered as a result of the autism peer support training. Two key themes emerged in relation to discussions about the difference this training programme makes: Life changing and Advocacy.

1. Life Changing

Analytical workshop discussions highlighted that some trainees may have never experienced such a sense of belonging or validation as they had on the autism peer support training course. A reflection offered by a member of the training team highlights ways in which the training programme provided a context for transformation by moving away from conventional deficit-based ideas about autism, prevalent within neuro-typical contexts. Instead, it provided people with autism the opportunity to feel validated, empowered and to develop an ‘autistic identity’:

“Whilst working as a trainer for Imroc on the autism peer support course I have noticed an effect on several trainees who did not receive a diagnosis until later in life. Post diagnosis they have received little support and have been left with a deficit-based interpretation of autism. They have not had a great deal of association with other autistic people and once they meet other autistic people, they gain a greater insight into themselves. Many of their differences have been compared to neuro-typical people and internalised as some kind of self-failing affecting their self-esteem. Once they are in an environment that moves away from the deficit-based concept of autism they begin to reevaluate themselves. Trainees have reported on several occasions that it has been life changing. They have felt empowered not only to create a better life for themselves but also to create a better world for other autistic people. The creation of an autistic identity has profoundly affected their sense of self-worth and confidence in a positive way.” (Trainer)

The training team spoke about a sense of pride that develops in relation to their hard work in contributing towards tangible outcomes of transformation, and the unique context the training provides to support this process.

Trainers added:

“I’m so proud of the whole team and everyone’s role within it” (Trainer)

“I think it’s good to be reminded how reframing this training is and how unique what we are all doing… And how powerful lived experiences are and how we can use them to help others.” (Trainer)

“I think there are often different outcomes, professionals may just get a certificate to practice. But autistic people often have a much more profound journey and begin to build an autistic identity and take pride in their self.” (Trainer)

The training team acknowledged there is a need to capture further evidence about the transformational nature of the course such as through self-reporting and feedback from trainees, conversations within the trainer/trainee cohorts, trainer observations, informal feedback logs and course completion reflection sessions.

2. Advocacy

The programme motivated participants to advocate for themselves and others, creating ripple effects beyond individual transformation. Trainees reported feeling empowered to challenge medical negligence, rewrite organisational policies for accessibility, and create more supportive environments for peers. This advocacy work represented a key motivation for both trainees and trainers.

One trainee reflected:

“I was very fortunate to meet other autistic women after my late-diagnosis through a local peer support group and completing the pilot course helped me reflect on the support this gave me… with the view that going on to help deliver the training will hopefully open up these opportunities for autistic peer support more widely across the country… that’s one of the core end/ long-term goals for me I guess” (Trainer)

During analytical workshops, trainees were described as already being motivated within the course because they want to make a better world for autistic people. Trainee evaluation feedback echoed this, emphasising their desire to make a difference and give others the confidence to feel heard.

Trainees can thrive in autism peer roles

Progress: Some Confidence: Some

Although further evidence is required to fully explore post-training success, analytical workshop discussions and evaluation feedback highlighted two key factors influencing trainee experiences within their roles post-training. Firstly, the degree of support, development opportunities and supervision offered to them, and secondly whether services are adequately prepared for autism peer support roles.

1. Organisational support and supervision

Success in peer support roles depends significantly on adequate supervision, development opportunities, and organisational preparedness. The training team reflected on the risk identified in the context mapping that organisations may not adequately support trainees or understand the training or role. In addition, when people are in peer support roles, they may not get the supervision they need. Trainees could be better prepared for that by including further training around this in the course.

Additionally, trainers identified that future course material could better emphasise peer support worker wellbeing and how they can recognise and prioritise their own needs in the workplace, including within the context of supervision:

“This feels really crucial when considering autistic people, especially thriving in the workplace as peer support workers – that ability to maintain their own wellbeing and the need for supervision to support with this once they are into a working role” (Trainer)

Trainers talked about the importance of having supportive employers and roles for the trainees to go into after the programme to enable them to thrive.

The evaluation identified gaps in organisational engagement during training, with some managers/employers providing insufficient support throughout the programme. Enhanced organisational preparation, including clear expectations, regular communication, and structured pathways into roles, could improve outcomes.

Although a lot of work already goes on to effectively work with organisations, the training team suggested further ways to enhance this process. These included:

Providing a FAQ sheet and video to prepare trainees from the outset through to the outcome and beyond.

Asking for further support from the organisation that sent the trainee.

Providing organisations with clear information about what is required from the trainee.

Communication from past trainers to talk about their post-training roles e.g. through video testimonies or online calls.

Highlighting clearly the pathway through the training into roles and including learning mentors in future cohorts.

It was suggested that obtaining organisational feedback after trainees completed the course would be beneficial (e.g. benefits, differences they have seen and whether they thought it was worthwhile). Following up trainees about their experiences post-training would also provide important evidence about factors supporting or impeding their ability to thrive within their roles.

2. Are services ready for autism peer support roles?

A critical factor in post-training success is whether services are adequately prepared for autistic peer support workers. In order for peer support workers to thrive in their work after the training course, there must be roles for people to go into, and organisations must have the funding to develop and properly support such roles. Many people who complete the autism peer support training programme do not immediately step into autism peer support roles. The training team reflected that part of the wider programme of work is highlighting the need for organisational education about autism and peer support values.

Services must be equipped to support authentic self-expression, provide necessary adaptations, and value the unique contributions of autistic peer support workers. This represents a systemic challenge requiring ongoing attention beyond individual training.

This evaluation demonstrates that the autism peer support worker training programme effectively delivers its intended outcomes and creates transformative experiences for participants. The programme represents more than professional development – it provides opportunities for personal growth, identity development, and community building within a neuro-affirming environment.

A huge amount of work, preparation and continual development has gone into setting up and co-producing the pilot and formal training programme. This evaluation provided strong evidence of the on-going improvements within future iterations of the programme, with issues highlighted in course material and delivery of the 2022 training being developed and improved in 2023. This process was a direct result of the care and attention taken to be responsive to people’s diverse and individual needs in the context of co-producing a unique and innovative training programme. It also reflected the clear dedication of the training team to continually refine, adapt and adjust the course in relation to feedback. This process was described as ongoing as the team are “constantly looking for ways to improve.”

The training team are passionate about the work they do. They adopt and deeply integrate the Imroc values into training delivery and embody reciprocal learning based on sharing personal lived experience. This creates safe spaces for participants to explore and develop their personal and professional identities. The stories people shared, both as trainees and trainers, indicate that being part of this programme has the potential to be life changing. It may give people the opportunity for the first time in their lives to feel safe enough to be themselves, to feel ‘neuro-affirmed’, to build trust together and experience reciprocity.

Creating such safe, neuro-inclusive personalised and trauma-informed spaces, however, is a challenging task which involves a huge amount of preparation, teamwork and ability to hold complexity. A key realisation for both trainees and trainers is the diversity of backgrounds, needs, experiences and ways of learning and expressing within trainee cohorts. Responding to the personalised nature of learning requires on-going attention and sensitivity to detail within the learning environment which, as one person expressed, could be exhausting for the ‘neurotypical’. The online nature of the course could at times exacerbate such challenges, however a great deal of attention has gone into ensuring that despite technical issues, the training team has been able to respond and adapt to feedback to ensure this learning platform can feel as user-friendly as possible.

The evaluation, being based on the Theory of Change model, highlighted the importance of gauging the feelings of trainees during their learning journey. Because the training programme places a huge emphasis on building trust, this enables many trainees to go through a form of personalised developmental process, reaching sometimes profound realisations about themselves and their identity, during what is sometimes referred to as ‘unmasking’. Evidence suggested this as a key to supporting learning, therefore identifying a potential key mechanism for change within this context. As a consequence, trainees were able to engage more fully in the training programme, demonstrating greater ability to understand and apply values and principles, and reflect upon themselves and their experiences more openly.

Revisiting risks and assumptions

Many of the assumptions (outlined in Figure 3) have been supported with evidence throughout the findings section; for example that the training is updated and developed in relation to changes and feedback, that trainers have the appropriate knowledge, skills and experience to create a safe and supportive training experience, that training is aligned to the Capability Framework and that the training is delivered well online, despite technical issues that do arise and were more prominent in the 2022 cohort.

The evaluation highlighted that there are a few risks and assumptions that require careful on-going consideration. These concern two key themes, as outlined below:

1. Trainer support

A major risk identified from the context analysis was that trainers can feel anxious, exhausted or overwhelmed at meeting complex and diverse needs. This risk was confirmed within the evaluation findings. At the same time, a related assumption about Imroc having robust mechanisms for trainer support was also demonstrated, with trainers frequently mentioning the supportive nature of the training team. This may require on-going considerations, however, taking into account the intensity and complexity of holding safe, personalised, neuro-informed spaces. It also may involve further reflection around the question of whether trainers have enough time to fully understand and continually respond to the learning needs of trainees. The autism peer support training environment can be demanding, and the time and processing needs of both trainers and trainees is a crucial consideration.

2. Organisational support

Further risks identified in the context analysis highlighted the importance of the role of organisations, their engagement within the training process, their support for trainees and their understanding of autism peer support worker roles. Although some good progress has been made in engaging organisations, this evaluation identifies these risks to be on-going considerations and highlights the need for further data when trainees go on to undertake their roles.

For autism peer support roles to be effectively implemented in practice, organisations need to carefully consider how the role will be supported, supervised and developed. As well as creating a safe environment for peer support workers, organisations can cultivate clear and shared understandings about the meaning and purpose of this role and its inclusion within their culture (Repper et al., 2021).

This evaluation demonstrated that employing organisations were not always fully engaged, and that there was ambiguity about how well-supported trainees would be once entering their peer support roles. Imroc have therefore initiated a concurrent evaluation focusing on post-training experiences to address this gap. This evaluation aims to collect data about the number of trainees who transition into peer support roles, how well the training prepares them for the role and the level of confidence it provides in offering peer support. The evaluation will also explore areas that may have been missing in the training, the challenges faced by individuals who did not complete the course, and the support trainees receive from nominating organisations.

Recommendations

The following recommendations aim to build upon the programme’s demonstrated success while addressing identified areas for enhancement and ensuring sustainable, positive outcomes for all participants.

1. Enhanced organisational engagement

Expand recruitment from diverse organisations and promote understanding of autism peer support worker roles throughout the training journey. Greater diversity could be facilitated through dissemination of evaluation findings and marketing the programme’s unique successes.

2. Improved trainee preparation

Further develop pre-programme preparation initiatives, building on demonstrated improvements between 2022 and 2023 cohorts. This includes emphasising Q&A meeting attendance, providing FAQ sheets and videos about programme expectations, and addressing diverse trainee backgrounds and needs.

3. Robust trainer support systems

Ensure trainers have ample time and support around potential overwhelm, anxiety and stress that can be involved in building safe, neuro-inclusive, personalised environments for learning. It is essential to acknowledge the challenges trainers experience and to consider on-going developments in helping them to feel safe and supported including broader staff wellbeing initiatives.

4. Post-training support and organisational preparation

Better prepare trainees for post-training challenges, including information about different role types, wellbeing management, supervision needs, and organisational navigation. Enhanced work with organisations to improve preparation for autism peer support worker roles, including employer involvement and understanding of programme integration. Resources could be developed for employing organisations about autism peer support integration.

5. Enhanced evaluation data collection

Capture additional evidence through reflective learning logs documenting change aligned with theory of change stages, more rigorous monitoring of trainee feelings and safety perceptions, robust measurement of personal development outcomes, and detailed exploration of post-training impact and skill application.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank everyone involved who contributed to this report, in particular the on-going support and mentorship from Matter of Focus (Ailsa Cook, Simon Bradstreet and Miriam Scott-Pearce). Many thanks to the Autism Peer Support Training Programme Lead at Imroc, and to all of the committed autism peer support trainers who shared their invaluable personal and learning experiences. Many thanks also for the support and feedback from members of Imroc’s Research, Evaluation and Development team.

-

Bradstreet, S. & Buelo, A. (2023). Imroc peer support theory and practice training: An independent evaluation. Matter of Focus. Available at: https://www.matter-of-focus.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/IMROC-Evaluation-November-2023.pdf

Charles, A., Nixdorf, R., Ibrahim, N., Meir, L. G., Mpango, R. S., Ngakongwa, F., … & Mahlke, C. (2021). Initial training for mental health peer support workers: Systematized review and international Delphi consultation. JMIR Mental Health, 8(5), e25528.

Health Education England, Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, and Skills for Care (2022). The Capability Framework for Autism Peer Support Workers [Draft]. Available at: https://www.oxfordhealth.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/sites/21/2022/04/APSW-Capabilities-SHARING-DRAFT.pdf

Mead, S., Hilton, D., & Curtis, L. (2001). Peer support: a theoretical perspective. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 25(2), 134.

NHS England (2019). The NHS Long Term Plan. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-plan

Repper, J., Aldridge, B., Gilfoyle, S., Gillard, S., Perkins, R., & Rennison, J. (2013). Peer support workers: Theory and practice. London: Centre for Mental Health.

Repper, J., Walker, L., Skinner, S., & Ball, M. (2021). Preparing organisations for peer support: creating a culture and context in which peer support workers thrive. Imroc Briefing Paper, 17.

Slade, M., McDaid, D., Shepherd, G., Williams, S., & Repper, J. (2017). Recovery: the business case. Imroc Briefing Paper, 14.

Watson, E., & Repper, J. (2022). Peer Support in mental health and social care services: Where are we now?. Imroc Briefing Paper, 22.